Poema de Bobbie Lindquist -Octi the Octopus-

Published Wednesday, April 27, 2005 by Spyder.Octi the Octopus

Octi is an octopus

Octi is an octopus

he lives down in the sea

off the coast of california

and close by me.

He is just a little guy

not bigger than a pinch

the fact is quite simple

he is only an inch

Octi moves around the sea

swaying to and fro

because he has no backbone

to hamper his free flow

He has a wonderful brain

inside his little head

trial and error is his way

to solve problems, it is said

Octi remembers what he does

like an elephant, never forgets

so when the problem comes again

he solves it, doesn't fret

He has a lot of legs

eight to be exact

and each one has some suckers

and this is quite a fact

When threatened by an enemy

Octi can escape

by releasing clouds of purple ink

and a getaway he can make

You can tell how Octi is feeling

by the color of his skin

white is fear, red is anger

and brown is where he will begin

Labels: Poemas

Pulpos y Graffitis (II) -Ensoe-

Published Saturday, April 23, 2005 by Spyder.Arte y pulpos -Hawley-

Published Thursday, April 21, 2005 by Spyder.

El cuadro perteneca al matrimonio que forman los artistas Christopher y Deborah Hawley.

Labels: Artistas

Valor nutritivo del pulpo

Published Wednesday, April 20, 2005 by Spyder.En comparación con el resto de mariscos, el pulpo es poco calórico, y su contenido en colesterol, proteínas y grasa es bajo. La carne de pulpo tiene un sabor excelente debido a su alimentación.

Entre los minerales, destaca el aporte de calcio, que es el más alto de todos los mariscos. El calcio es un constituyente de huesos y dientes, interviene en la coagulación sanguínea y es necesario para la transmisión del impulso nervioso.

La vitamina más destacable es la A, que favorece la resistencia a las infecciones y es necesaria para el desarrollo del sistema nervioso. Aporta también una cantidad considerable de vitamina B3 y menores cantidades de vitaminas B, y B2.

Labels: Gastronomía

Cocina -Pepinos con pulpo al tequila-

Published Monday, April 18, 2005 by Spyder.

Ingredientes:

1 pepino grande derecho (lo mas posible)

1 vaso de tequila

1 pulpo pequeño crudo

1 vaso de jugo de naranja

2 cuch sopera de mirin o vinagre c/azucar

1 cuch de aceite de ajonjoli

1 cuch de sal fina

2 cuch salsa de soya

1 cuch de ajonjoli tostado

Preparado:

Se limpia el pulpo con sal, se enjuaga y se pone a cocer en una olla con agua durante 20 minutos y se deja reposar colgado al aire por 1 hora en la cocina y despues se rebana en bocadillos. el pepino se rueda sobre una tabla para picar con sal para que se desfleme haciendo que se introduzca la sal dentro del mismo, despues se le quitan las semillas de adentro por un solo lado con un cuchillo, dejandolo en forma de vaso, en el cual se le vierte 1 vaso de tequila y se deja

reposar parado con el tequila dentro en el refrigerador. Por Jorge Gonzalez Attolini

1 pepino grande derecho (lo mas posible)

1 vaso de tequila

1 pulpo pequeño crudo

1 vaso de jugo de naranja

2 cuch sopera de mirin o vinagre c/azucar

1 cuch de aceite de ajonjoli

1 cuch de sal fina

2 cuch salsa de soya

1 cuch de ajonjoli tostado

Preparado:

Se limpia el pulpo con sal, se enjuaga y se pone a cocer en una olla con agua durante 20 minutos y se deja reposar colgado al aire por 1 hora en la cocina y despues se rebana en bocadillos. el pepino se rueda sobre una tabla para picar con sal para que se desfleme haciendo que se introduzca la sal dentro del mismo, despues se le quitan las semillas de adentro por un solo lado con un cuchillo, dejandolo en forma de vaso, en el cual se le vierte 1 vaso de tequila y se deja

reposar parado con el tequila dentro en el refrigerador.

Al dia siguiente, desechas el tequila o te lo tomas y le quitas la cascara para despues picarlo o rebanarlo en rodajas a las cuales se agregas el vinagre "mirin" o vinagre suave con poco azucar y pizca de sal y lo revuelves todo con la salsa de soya, la cuch de aceite de ajonjoli, el vaso de jugo de naranja y el pulpo. lo decoras con el ajonjoli tostado y listo, la botana ya esta preparada.

Labels: Gastronomía

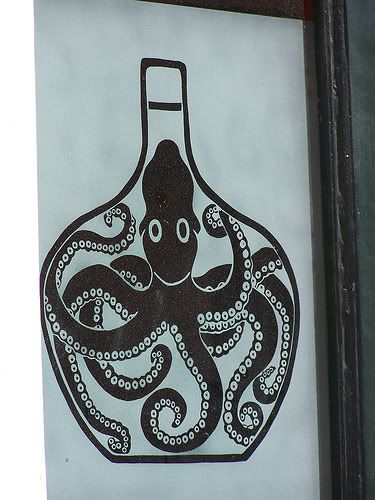

Fotografías de pulpos -Genio en la botella-

Published Thursday, April 14, 2005 by Spyder.

Este genio de la botella parece que tenga resaca...

Fotografía sacada de la web de submarinismo Scuba Board

Labels: Fotografías

Pulpo -Genie in a bottle-

Published Wednesday, April 13, 2005 by Spyder. Oh... I feel like I've been locked up tight

Oh... I feel like I've been locked up tight For a century of lonely nights

Waiting for someone

To release me

You're licking your lips and blowing kisses my way

But that dont mean I'm gonna give it away

Baby, baby, baby

(baby, baby, baby)

Oh whoa...

My body's saying let's go

Oh whoa...

But my heart is saying no (no)

If you wanna be with me, baby

There's a price you pay

I'm a genie in a bottle

You gotta rub me the right way

If you wanna be with me

I can make your wish come true

Christina Aguilera -Genie in a bottle-

Labels: Curiosidades, Fotografías

Pulpos y literatura -Luis María Pescetti-

Published Tuesday, April 12, 2005 by Spyder. El pulpo está crudo.

El pulpo está crudo.Luis María Pescetti

El pulpo está crudo contiene doce relatos breves impregnados de imaginación y humor, con diálogos descabellados. Historias disparatadas que divierten hasta provocar la risa, como la de un chico que comía flores o la de una pelea entre dos delirantes archisúperenemigos. Ilustraciones de O’Kif. Buenos Aires, Editorial Alfaguara, 1999. Colección Infantil, Serie Morada. Publicado también en España en la colección Alfaguay (Madrid, Alfaguara, 2000).

Luis María Pescetti

Nació en San Jorge, provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina, en 1958. En Buenos Aires se recibió de Musicoterapeuta (Diploma de Honor) en 1979. Realizó estudios de: piano, canto, pedagogía musical, armonía y composición. Trabajó como Musicoterapeuta en rehabilitación de mujeres operadas de mama y con pacientes psiquiátricos, niños y adultos. Fue profesor de música en preescolar, escuelas primarias, secundarias, y Universidades.

Para seguir leyendo su biografía en su página personal.

Labels: Literatura

Pesca de pulpos -Octopus fishing in Tokelau-

Published Monday, April 11, 2005 by Spyder.Un artículo que cuenta la leyenda de la que hablábamos ayer, y habla un poco de la pesca de pulpos realizada por mujeres en el archipiélago de Tokelau. Estas islas son bastante pobres al ser independientes de Nueva Zelanda, y hace unos años para mejorar su economía saltó a la fama al comercializar su dominio de Internet (tk).

OCTOPUS FISHING IN TOKELAU

By Anna Tiraa-Passfield

Published in Cook Islands

NewsJuly 1, 1999

Tuolo mai feke te pilipili kavei valu e tuolo,

Mai tuolo mai.

Ko nohonoho i lo kaoa

Fakalongona ake pule kua, hoa, hoa, hoa.

"Crawl out, little squid, with eight legs,

Crawl out, crawl out.

You stay in your hole

When you hear the sound, hoa, hoa, hoa, of the crab, crawling."

-- A song formerly sung by Tokelauan men to entice the feke from the hole.

-- A song formerly sung by Tokelauan men to entice the feke from the hole.

Tokelau is comprised of three low-lying atolls. These atolls, Fakaofo, Nukunonu and Atafu, stretch in a northwesterly direction from 9° 23' S, 171° 14' W for a distance of 170 km to 8° 30' S, 172° 30' W. The southern most atoll of Fakaofo is 65 km from Nukunono, with a further 105 km to Atafu, the northern most atoll.

Women's Fishing

Several people on Fakaofo have commented that women's fishing is not as common today as it was in previous times. A household questionnaire done in 1998 revealed that women fished on average two hours per week. Gleaning for octopus (feke) is one of the few types of fishing activity practiced by women. Other types include clam and rod fishing in the lagoon area. Octopus fishing is a favored and skilful activity undertaken particularly by women of Fakaofo, though men and children also engage in this activity.

Octopus Fishing

There are several traditional methods of catching feke in Tokelau. One, once commonly practiced by men, was described to me by an elderly male informant. This method utilized an octopus lure (puletakifeke) made from cowry shells of genera Cyparea and Ovulum. The shells were somehow arranged in the shape of a rat. This stems from a famous Polynesian legend about a rat and an octopus. The lure was apparently used by towing from a canoe along the reef in the lagoon. Small pebbles are placed in the shell, which rattles to attract the feke's attention.

The common method of feke fishing is mainly done during the day at low tide on the reef. A gagie (Pemphis acidula) stick or a metal rod of about 1 m in length is pushed into a likely kaoa (coral hole occupied by octopus) which may house the feke. The stick normally works by drawing out the animal as its tentacles one by one wrap around the stick. Once the head appears, the gatherer works quickly seizing it around the head with their hand. Within seconds, the feke is killed by biting between the eyes or turning its head inside out.

If the stick or metal rod is unsuccessful in drawing the feke from its hole, the body wall of the sea cucumber, locally called loli (Holothuria atra), is rubbed around the mouth of the kaoa. The bitterness of the loli draws the animal out. The hand is never used to move pebbles from the hole for fear of being bitten by a moray eel. The collected feke are strung on a metal wire or kalava (the outer skin of the top surface of the leaf stalk of a coconut frond), which is poked between the two holes (inhalant and exhalant siphons) located on either side of the head.

One informant told me that the greater catches of feke are taken on fakaiva ote mahina - the ninth phase of the moon (nine days after new moon), though they are caught throughout the year.

IDENTIFYING FEKE HOLES

The feke blocks the entrance to its kaoa by using its tentacles to gather a collection of coral pebbles. An experienced hunter can identify potential feke holes by the arrangement and recently disturbed appearance of the pebbles blocking the entrance. The arrangement of the pebbles is also seen as an indicator of the direction the feke has taken if it has vacated a hole. For example, if the pebbles lie to the left of the hole, the feke moved in the right direction and visa versa. When a feke is removed from its hole, it is often reoccupied by another. Experienced hunters will memorize the location of the hole for subsequent visits to inspect for reoccupation by another feke.

If the water is disturbed by turbulence, coconut meat is chewed and spat out onto the water surface. The coconut oil smoothes the water surface, enabling the woman to view clearly beneath the shallow waters for potential kaoa.

Uses

Feke are caught for subsistence purposes and bait for catching certain fin fish. Preparation for consumption is done by baking in the umu (traditional out house oven), boiling by mixing with other ingredients for additional flavor (e.g. curry, coconut cream, onions, herbs) or boiling and then sun dried. Before cooking, the meat is tenderized by beating with the gagie wood or a stone. Another method for tenderizing the meat is by wrapping it in pawpaw (papaya) leaves and adding to boiling water.

Anna visited Tokelau whilst her husband Kelvin was carrying out an SPC-sponsored assessment of inshore fishery issues on Fakaofo.Anna is a Cook Islander and until recently managed a conservation project on Rarotonga. She is now based in Samoa and can be contacted (as of July 1999) through passfield@lesamoa.net.

Labels: Pesca

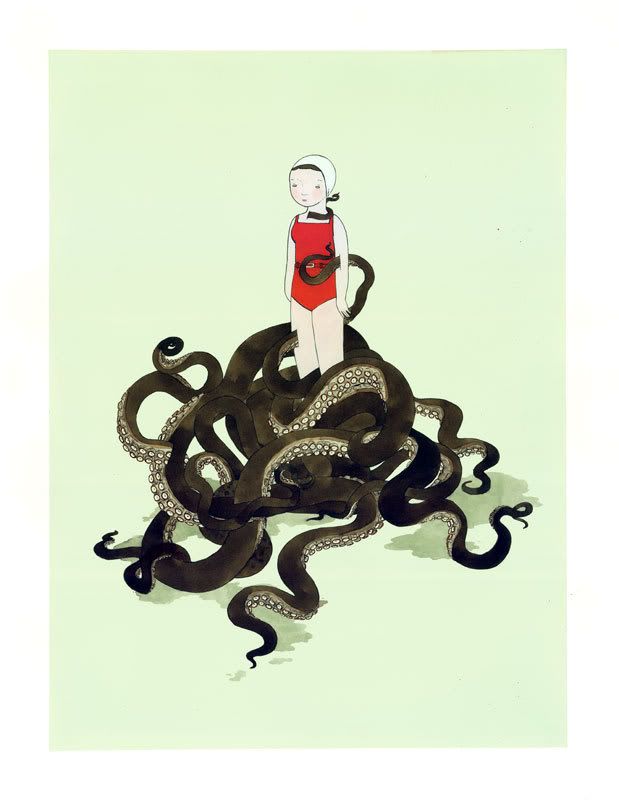

Arte y pulpos -Jen Corace-

Published Sunday, April 10, 2005 by Spyder.

Las ilustraciones son del ilustrador americano Jen Corace. Y suelen representar cuerpos de niños o niñas con una aparente frialdad en sus rostros.

Su página se puede visitar aquí. Es una página bastante completa y hasta tiene una sección de sencillos juegos versionados por Corace.

Leyendo el comentario que pone Corace en su perfil, parece que el artista es un poco disperso.

"Jen Corace is an artist and reelance illustrator who lives and Works in Providence, Rhode Island. Originally from the suburbs of southern New Jersey, she eventually made her way to the Rhode Island School of Design and graduated with a BFA in illustration.

Since then she’s been spending time here and there… moving… travelling… walking. She concerns herself with Victorian era photographic portraiture, reading up on any and every animal, eating toast and securing large amounts of personal space. While she hasn’t lived in a suburb in over thirteen years she draws a lot of her imagery and inspiration from the eighteen years that were spent in New Jersey. With a background in Illustration, Jen’s work is often narrative in nature and explores the juxtaposition of developed environments against more rural settings.

Professionally, Jen has worked with clients that include If’n Books and Marks, Chronicle Books, Galison/Mudpuppy, The Portland Mercury, Sound Collector Audio Review, and Cricket Magazine. While she generally creates pieces for design and print, Jen has also had her hand in the web design for the public art commission. The Color of Palo Alto. On the gallery side of things, she is represented by Motel in Portland, Oregon. She has shown from Providence, to Portland, to Los Angeles and has her first solo show at Motel in November 2005."

Labels: Artistas

Gif -Pulpo y el stress-

Published Saturday, April 09, 2005 by Spyder.Pulpos en el cielo -The Flying Octopus-

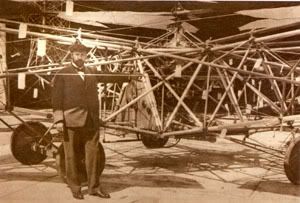

Published Tuesday, April 05, 2005 by Spyder.En los albores de la aviación un prototipo de helicóptero surcó los aires. Fue bautizado como The Flying Octopus.

The Flying Octopus

By C. V. Glines

By C. V. Glines

Most aviation historians agree that Igor I. Sikorsky deserves credit for designing, building, and flying the first practical helicopter. His XR-4, the first rotary-winged aircraft accepted by the Air Force, weighed 1,900 pounds and could lift 500 pounds of payload. It first flew in January 1942 and was demonstrated to Gen. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold the next July. General Arnold liked what he saw. "The Army Air Force," said he, "has taken flyers before with not so much gain promised."

One "flyer" to which General Arnold may have been referring was an earlier helicopter venture. Sikorsky's helicopter was not the first bought by the organization that would eventually become the United States Air Force. World War I had stimulated many to explore the possibility of true vertical flight. None had solved the riddle of stability, but the potential of vertical lift machines for military purposes continued to interest many.

Among these were a few officers of the Army Air Service who had become intrigued with the writings of a Russian with a French name: Dr. George de Bothezat. De Bothezat, a scientist who had fled the Bolshevik Revolution, was a big, bearded man with a quick wit and a violent temper. He was also an extreme egotist who once boasted publicly, "I am the world's greatest mathematician and scientist."

In Russia, de Bothezat had gained international renown for his theories about vertical flight. He had earned degrees in five countries and had published two acclaimed theses: "General Theory of Blade Screws" and "Theory of Helicopter Stability." Both found their way to the library of the Air Service Engineering Division at McCook Field, near Dayton, Ohio.

Throughout much of 1921 and 1922, the project was shrouded in secrecy, but on December 18,1922, Dr. George de Bothezat's assistants rolled out the "Flying Octopus" for its first test at McCook Field, near Dayton, Ohio, observed closely by de Bothezat (at left, in dark suit) and curious onlookers in and on top of the experimental craft's hangar.

In the early 1920s, McCook Field was the Air Service's engineering and flight test center. Workers investigated, researched, and developed any idea that might prove useful to the nation's young air arm. Maj. Thurman H. Bane, chief of the Division, read de Bothezat's treatises and felt that the theories had merit. He asked his superiors for permission to contact de Bothezat and invite him to Dayton. Permission was granted, and the Russian emigre was delighted to accept.

After de Bothezat arrived in Dayton, Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick, Chief of the Air Service, authorized a contract with him, without open bidding, for the construction of a helicopter. This unusual procedure was authorized because no other qualified bidders existed. However, de Bothezat first had to produce a written proposal to make the transaction legal.

Putting It on Paper

De Bothezat was exasperated by this bit of Army red tape, but he nevertheless submitted an eighteen-page letter. "The helicopter here disclosed," it stated, "is. . . to possess all qualities of inherent stability and maneuverability which are essential for the navigation of any vehicle of locomotion. The helicopter considered is essentially composed of four lifting blade screws identical in size and shape and disposed cross-wise."

The letter, accompanied by drawings and diagrams, further described the principles of operation and structure of the craft. General Patrick was impressed. In the 1921 budget, Congress appropriated the astonishing sum of $200,000 for work on the project. De Bothezat was hired as acting chief of the Engineering Division's Special Research Section at an annual salary of $10,000. The government specified that de Bothezat was to produce "drawings and data to design, construct, and supervise flight tests of a helicopter." In turn, the government was to provide engineering assistants, materials, equipment, arid hangar space.

When the Engineering Division received the first set of drawings and computations from de Bothezat, he was to receive $5,000. When the machine was fully constructed, he would receive another $4,800. If it actually left the ground, climbed to 300 feet, and returned to its takeoff point without mishap, he would receive further payments totaling $20,000. The craft was to be ready for flight by January 1, 1922--that is, in seven months.

To keep the curious away and allow de Bothezat and his assistants to work unmolested, the project was given "top secret" status. Work began in a tin-roofed hangar. When the machine began to take shape and outgrew the hangar, a wall of canvas was erected outside to enclose it from view.

Engineers assigned to work with de Bothezat enjoyed the task, despite the Russian's angry outbursts when things didn't go his way. He hovered over their workbenches, watching them turn his drawings into strangely shaped pieces of metal. He spent his waking hours tinkering, figuring, and writing furiously.

The existence of a top secret project right under their noses caused curious McCook test pilots to try to sneak a look at "the thing." Some took to the air to spy on the "mad scientist." At the end of routine test flights, they would swoop low and marvel at the crazy collection of tubing and blades. De Bothezat would shout curses in Russian and shake his fists, but the pilots merely waved back. Several VIPs were allowed to view the machine, however. These included former Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, and Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell.

Toward the end of 1921, de Bothezat realized he could not meet the deadline and pleaded for more time. He got an extension, and he and his assistants worked through the winter, spring, and summer, inching toward the day of reckoning. By the fall of 1922, the Air Service's first helicopter was near completion. On December 18, 1922, the machine was ready for the world to see.

Spectators quickly gathered around McCook Field as word of the aircraft spread. It had snowed the day before, but it was now sunny, with virtually no wind. Just after 9:00 a.m., the canvas walls parted, and de Bothezat's crew pushed their pride and joy to the center of the field.

Airborne Octopus

Several spectators gasped, snickered, and then broke into loud guffaws. They saw a strange framework of tubes and wires built into the shape of a giant cross, hung together with a spidery network of pulleys, chains, and metal strands. Four giant, six-bladed rotors were mounted on each end of the cross, and four other fans served as stabilizers. To an onlooker, the machine was a nightmare of steel and aluminum tubing, complicated gears, and guy wires.

Dr. de Bothezat's craft took the form of a giant cross with four identical six-bladed, horizontal rotors on each end. Four other fans worked as stabilizers. All of this was controlled through an elaborate network of gears, pulleys, chains, and guy wires. Shipping tags tied to the framework allowed engineers to observe airflow during test flights.

It was immediately dubbed "The Flying Octopus."

Thurman Bane (by then a colonel) had decided that he would serve as test pilot on the first flight. Taking his place in the pilot's seat, he slowly primed the engine. and started it. The huge contraption started to vibrate as the four giant rotors began to turn slowly like horizontal windmills.

As Bane opened throttle, de Bothezat and his crew stood clear. According to one McCook Field observer, "the movement seemed graceful and there was no noise of friction in any part of the machine. The craft began to lift itself a little--an inch, two, three--until it was about three feet above ground. It hovered at an altitude of two to six feet for one minute and forty-two seconds. Hovering at this height, the helicopter drifted some 300 feet with the wind. Having drifted close to a fence, [Colonel] Bane made a quick landing, which was done under complete control."

The powerplant in the "Octopus" was a 180-horsepower Le Rhone engine, later replaced by a 220-horsepower British Bentley Rotary, which rotated in a horizontal plane directly in front of the pilot's lap. Brig. Gen. Harold R. Harris, one of the helicopter's test pilots, once observed that "the Bentley Rotary was a good engine except that it had a bad habit of throwing cylinders. Fortunately, it never threw one while the tests were underway."

The controls were similar to those of the day's fixed-wing aircraft. A stick and rudder pedals controlled the pitch of the main blades, and an automobile-style steerwheel controlled the pitch of the three-bladed rotors mounted above the engine. A small hand throttle controlled the engine speed. There were so many gears, idles, and wheels to operate, said one test pilot, that not only looks like an octopus, it takes an octopus to fly it "

For example, the test pilot noted, "if the engine failed, the pilot had to reach forward to release the stop on the overall pitch wheel [and] grasp another wheel to adjust the pitch of the center stabilizing propellers so he could slow down the windmilling blades. At the same time, the pilot had to maintain lateral, longitudinal, and directional control with the stick. If he could do all this as he was falling, a fast twist was still needed on the main pitch control at the last minute to soften the landing."

General Harris recalled that "balancing the de Bothezat job. . . was really a tightrope walk in four directions."

The Flying Octopus accomplished all of its initial test objectives. In 1923, it carried increasingly heavier payloads and set an endurance record of two minutes and forty-five seconds. Nevertheless, the project was canceled when structural changes specified by the Army Air Service produced no substantial improvements in the aircraft's performance.

Weird, but Workable

Weird as the de Bothezat contraption looked, it made over 100 flights and accomplished all of its initial test objectives. On January 23, 1923, it left the ground with two people aboard and lifted a payload of 450 pounds to a height of four feet. The next month, it set an endurance record of two minutes and forty-five seconds. In April 1923, it lifted four men off the ground.

In the late spring of 1923, the government contracted with de Bothezat for an improved version of the helicopter The Air Service specified that he had to redesign the central part of the machine to give it strength and reduce size of the main rotors and make them less flexible. The changes, however, produced no substantial improvements in the aircraft's performance. Reluctantly, General Patrick ordered the project canceled.

In a long letter, Colonel Bane praised de Bothezat. "It is my sincere belief," said the officer, "that your helicopter is the biggest aeronautical achievement since the first flight of the Wright brothers." No less a personage than Thomas A. Edison, who had experimented with helicopters in the 1880s, told the Russian, "You certainly have made a great advance; in fact, as far as I know, the first successful helicopter. "

De Bothezat was keenly disappointed by the cancellation but went on to other projects. In 1936, he built another experimental model, which did not show marked improvement over the earlier version. Even so, he appeared before the House Military Affairs Committee that year to advocate continued helicopter research. He predicted that the chopper "would give rise to an entirely new method of warfare, battalions of swift and silently flying machine guns, able to land at night behind [an] enemy's lines."

On February 1, 1940, de Bothezat died in Boston following an emergency operation. He was fifty-eight. Long before then, de Bothezat's "Flying Octopus" had been sent to the McCook salvage yard. However, one rotor hub and four main blades have been preserved and are in the National Air and Space Museum's collection in Washington, D. C.

C. V. Glines is a regular contributor to this magazine. A retired Air Force colonel, he is a free-lance writer and the author of many books, most recently Attack on Yamamoto. His last article for AIR FORCE Magazine, "Their Finest Hour" appeared in the September 1990 issue.

Among these were a few officers of the Army Air Service who had become intrigued with the writings of a Russian with a French name: Dr. George de Bothezat. De Bothezat, a scientist who had fled the Bolshevik Revolution, was a big, bearded man with a quick wit and a violent temper. He was also an extreme egotist who once boasted publicly, "I am the world's greatest mathematician and scientist."

In Russia, de Bothezat had gained international renown for his theories about vertical flight. He had earned degrees in five countries and had published two acclaimed theses: "General Theory of Blade Screws" and "Theory of Helicopter Stability." Both found their way to the library of the Air Service Engineering Division at McCook Field, near Dayton, Ohio.

Throughout much of 1921 and 1922, the project was shrouded in secrecy, but on December 18,1922, Dr. George de Bothezat's assistants rolled out the "Flying Octopus" for its first test at McCook Field, near Dayton, Ohio, observed closely by de Bothezat (at left, in dark suit) and curious onlookers in and on top of the experimental craft's hangar.

In the early 1920s, McCook Field was the Air Service's engineering and flight test center. Workers investigated, researched, and developed any idea that might prove useful to the nation's young air arm. Maj. Thurman H. Bane, chief of the Division, read de Bothezat's treatises and felt that the theories had merit. He asked his superiors for permission to contact de Bothezat and invite him to Dayton. Permission was granted, and the Russian emigre was delighted to accept.

After de Bothezat arrived in Dayton, Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick, Chief of the Air Service, authorized a contract with him, without open bidding, for the construction of a helicopter. This unusual procedure was authorized because no other qualified bidders existed. However, de Bothezat first had to produce a written proposal to make the transaction legal.

Putting It on Paper

De Bothezat was exasperated by this bit of Army red tape, but he nevertheless submitted an eighteen-page letter. "The helicopter here disclosed," it stated, "is. . . to possess all qualities of inherent stability and maneuverability which are essential for the navigation of any vehicle of locomotion. The helicopter considered is essentially composed of four lifting blade screws identical in size and shape and disposed cross-wise."

The letter, accompanied by drawings and diagrams, further described the principles of operation and structure of the craft. General Patrick was impressed. In the 1921 budget, Congress appropriated the astonishing sum of $200,000 for work on the project. De Bothezat was hired as acting chief of the Engineering Division's Special Research Section at an annual salary of $10,000. The government specified that de Bothezat was to produce "drawings and data to design, construct, and supervise flight tests of a helicopter." In turn, the government was to provide engineering assistants, materials, equipment, arid hangar space.

When the Engineering Division received the first set of drawings and computations from de Bothezat, he was to receive $5,000. When the machine was fully constructed, he would receive another $4,800. If it actually left the ground, climbed to 300 feet, and returned to its takeoff point without mishap, he would receive further payments totaling $20,000. The craft was to be ready for flight by January 1, 1922--that is, in seven months.

To keep the curious away and allow de Bothezat and his assistants to work unmolested, the project was given "top secret" status. Work began in a tin-roofed hangar. When the machine began to take shape and outgrew the hangar, a wall of canvas was erected outside to enclose it from view.

Engineers assigned to work with de Bothezat enjoyed the task, despite the Russian's angry outbursts when things didn't go his way. He hovered over their workbenches, watching them turn his drawings into strangely shaped pieces of metal. He spent his waking hours tinkering, figuring, and writing furiously.

The existence of a top secret project right under their noses caused curious McCook test pilots to try to sneak a look at "the thing." Some took to the air to spy on the "mad scientist." At the end of routine test flights, they would swoop low and marvel at the crazy collection of tubing and blades. De Bothezat would shout curses in Russian and shake his fists, but the pilots merely waved back. Several VIPs were allowed to view the machine, however. These included former Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, and Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell.

Toward the end of 1921, de Bothezat realized he could not meet the deadline and pleaded for more time. He got an extension, and he and his assistants worked through the winter, spring, and summer, inching toward the day of reckoning. By the fall of 1922, the Air Service's first helicopter was near completion. On December 18, 1922, the machine was ready for the world to see.

Spectators quickly gathered around McCook Field as word of the aircraft spread. It had snowed the day before, but it was now sunny, with virtually no wind. Just after 9:00 a.m., the canvas walls parted, and de Bothezat's crew pushed their pride and joy to the center of the field.

Airborne Octopus

Several spectators gasped, snickered, and then broke into loud guffaws. They saw a strange framework of tubes and wires built into the shape of a giant cross, hung together with a spidery network of pulleys, chains, and metal strands. Four giant, six-bladed rotors were mounted on each end of the cross, and four other fans served as stabilizers. To an onlooker, the machine was a nightmare of steel and aluminum tubing, complicated gears, and guy wires.

Dr. de Bothezat's craft took the form of a giant cross with four identical six-bladed, horizontal rotors on each end. Four other fans worked as stabilizers. All of this was controlled through an elaborate network of gears, pulleys, chains, and guy wires. Shipping tags tied to the framework allowed engineers to observe airflow during test flights.

It was immediately dubbed "The Flying Octopus."

Thurman Bane (by then a colonel) had decided that he would serve as test pilot on the first flight. Taking his place in the pilot's seat, he slowly primed the engine. and started it. The huge contraption started to vibrate as the four giant rotors began to turn slowly like horizontal windmills.

As Bane opened throttle, de Bothezat and his crew stood clear. According to one McCook Field observer, "the movement seemed graceful and there was no noise of friction in any part of the machine. The craft began to lift itself a little--an inch, two, three--until it was about three feet above ground. It hovered at an altitude of two to six feet for one minute and forty-two seconds. Hovering at this height, the helicopter drifted some 300 feet with the wind. Having drifted close to a fence, [Colonel] Bane made a quick landing, which was done under complete control."

The powerplant in the "Octopus" was a 180-horsepower Le Rhone engine, later replaced by a 220-horsepower British Bentley Rotary, which rotated in a horizontal plane directly in front of the pilot's lap. Brig. Gen. Harold R. Harris, one of the helicopter's test pilots, once observed that "the Bentley Rotary was a good engine except that it had a bad habit of throwing cylinders. Fortunately, it never threw one while the tests were underway."

The controls were similar to those of the day's fixed-wing aircraft. A stick and rudder pedals controlled the pitch of the main blades, and an automobile-style steerwheel controlled the pitch of the three-bladed rotors mounted above the engine. A small hand throttle controlled the engine speed. There were so many gears, idles, and wheels to operate, said one test pilot, that not only looks like an octopus, it takes an octopus to fly it "

For example, the test pilot noted, "if the engine failed, the pilot had to reach forward to release the stop on the overall pitch wheel [and] grasp another wheel to adjust the pitch of the center stabilizing propellers so he could slow down the windmilling blades. At the same time, the pilot had to maintain lateral, longitudinal, and directional control with the stick. If he could do all this as he was falling, a fast twist was still needed on the main pitch control at the last minute to soften the landing."

General Harris recalled that "balancing the de Bothezat job. . . was really a tightrope walk in four directions."

The Flying Octopus accomplished all of its initial test objectives. In 1923, it carried increasingly heavier payloads and set an endurance record of two minutes and forty-five seconds. Nevertheless, the project was canceled when structural changes specified by the Army Air Service produced no substantial improvements in the aircraft's performance.

Weird, but Workable

Weird as the de Bothezat contraption looked, it made over 100 flights and accomplished all of its initial test objectives. On January 23, 1923, it left the ground with two people aboard and lifted a payload of 450 pounds to a height of four feet. The next month, it set an endurance record of two minutes and forty-five seconds. In April 1923, it lifted four men off the ground.

In the late spring of 1923, the government contracted with de Bothezat for an improved version of the helicopter The Air Service specified that he had to redesign the central part of the machine to give it strength and reduce size of the main rotors and make them less flexible. The changes, however, produced no substantial improvements in the aircraft's performance. Reluctantly, General Patrick ordered the project canceled.

In a long letter, Colonel Bane praised de Bothezat. "It is my sincere belief," said the officer, "that your helicopter is the biggest aeronautical achievement since the first flight of the Wright brothers." No less a personage than Thomas A. Edison, who had experimented with helicopters in the 1880s, told the Russian, "You certainly have made a great advance; in fact, as far as I know, the first successful helicopter. "

De Bothezat was keenly disappointed by the cancellation but went on to other projects. In 1936, he built another experimental model, which did not show marked improvement over the earlier version. Even so, he appeared before the House Military Affairs Committee that year to advocate continued helicopter research. He predicted that the chopper "would give rise to an entirely new method of warfare, battalions of swift and silently flying machine guns, able to land at night behind [an] enemy's lines."

On February 1, 1940, de Bothezat died in Boston following an emergency operation. He was fifty-eight. Long before then, de Bothezat's "Flying Octopus" had been sent to the McCook salvage yard. However, one rotor hub and four main blades have been preserved and are in the National Air and Space Museum's collection in Washington, D. C.

C. V. Glines is a regular contributor to this magazine. A retired Air Force colonel, he is a free-lance writer and the author of many books, most recently Attack on Yamamoto. His last article for AIR FORCE Magazine, "Their Finest Hour" appeared in the September 1990 issue.

Labels: Camisetas, Monstruos marinos, Pulpos celestes