Erotismo con pulpos -Juguete Hentai-

Published Sunday, February 27, 2005 by Spyder.Erotismo con pulpos -Tentacle Porn-

Published Saturday, February 26, 2005 by Spyder.Sin duda uno de los artículos más completos sobre la pornografía tentacular. Ahí todos los octófilos encontrarán las respuestas.

Via blog de The Emperor

Tentacle Porn

I often use tentacle porn as an example of the strangeness of the Internet (in that it caters for just about every strange desire someone may ever have) but what is it? It essentially invovles the usually non-consensual penetration. The main site for this kind fo thing is Shokushu High School, which contains an awful lot of high quality anime/manga drawings of very distrubing sex acts (as well as some really poor quality photomanpilualtions) and The Xenophile, which has more amateurish drawings (which for me is more unsettling). There are also connections with vore (which is getting your kicks from being eaten) sites like Chupacabras Dark Domain. All pretty unsavoury and the kind of thing that psychopaths might get off on but that doesn't explain its widespread popularity (and trust me - it is big, even 'mainstream', in Japan). Where it has really gone overground is in a number of manga films most famously with the Urotsuki Doji Saga which includes the infamous "Legend of the Overfiend" described here as:

quote:

... the the most famous tentacle rape and super-violent horror in the history of anime.

Other examples include "La Blue Girl" which started off animated and span off a live action version. Fully live action is the series of films (there seem to be 5) called Injukyoshi which impresively translates to "Obscene Beast Teacher". And if there needed to be any other sign of how widespread it is there is even gay tentacle porn The main reason for this is that hentai (anime porn) by convention doesn't show penises (technically the Japanese censorship laws don't allow the depiction of male or female genitals or pubic hair) and so inventive anime authors and artists have used the tentacle as a replacement - see this everything2 entry for further explanation. An interview with Toshio Maeda, the creator of the and describe elsewhere in the piece as "the master of tentacle violation", gives his overview of how it came about :

quote:

CJ: Can you talk about how the tentacle came to be used in your work? TM: At that time [pre-Urotsuki Doji], it was illegal to create a sensual scene in bed. I thought I should do something to avoid drawing such a normal sensual scene. So I just created a creature. [His tentacle] is not a [penis] as a pretext. I could say, as an excuse, this is not a [penis], this is just a part of the creature. You know, the creatures, they don't have a gender. A creature is a creature. So it is not obscene - not illegal. Drawing intercourse was, and is, illegal in Japan. That is our big headache: to create such a sensual scene. We are always using any type of trick.

Which explains it but it doesn't make it right. In fact in a recent development Motonori Kishi was charged with obscenity for producing manga which failed to conceal the genitals:

quote:

"Bodies were drawn in a lifelike manner with little attention to concealment (of genitalia), making for sexually explicit expression and deeming the book pornographic matter," Mr Nakatani said.

Tentacle porn also crops up in a more light-heartd way with various Cthulhu sites looking into this area (although Cthulhu Sex.com doesn't):

· Cthulhu Myth Hoes

· alt.sex.cthulhu archive It also crops up in The Lighter Side of Tentacle Hentai and is a recurring theme at Ghastly's Ghastly Comic which has the strapline: 'Tentacle Monsters and the Women Who Love Them' (they also sell a range of merchandise through Cafepress but who'd want to wear something like that? Well not until they make it available on a black T shirt anyway). It has even made an appearance in a Weebl and Bob cartoon!! And don't think this hasn't intruded into the mainstream!! There is currently furore over the display of the Victorian painting 'The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife' by David Laity as detailed by NEWS.com.au which is a redrawing of Hokusai's original woodcut (reproduced below - translation of the text): This reworking continues to the modern day - as part of his 'Waves and Plagues' collection Masami Teraoka has also brought this up to date with his 2002 work "Sarah and Octopus/Seventh Heaven" which uses traditional art forms like ukiyo-e to address modern themes (his work has been covered in the documentray The Floating World). It may have also influenced Toshio Saeki's "Octo-girl". I also stumbled across a modern silk screen print inspired by it. Worryingly it has been inspired Hokusai manga aka Edo porn a 1981 film giving an erotic version of Hokusia's life with an eye opening reconstruction of the famous painting. While that is bordering on the laughable there are more disturbing examples of women and octopus "sex" (and yes you should think twice before clicking that link) although its unclear if the inspiration was directly from Hokusia (or even how alive the octopus is leading to accusations of necroctoporn). Rather than being some kind of backroom kinkiness tentacle porn is widely available in Japan and although the above is shunga (shunga were the illustrations to erotic books, etc.) Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is better know for his landscapes (and his woodcuts are very well known) and he apparently coined the term manga (which means "whimsical sketches"). Its probably western European puritanism which insists on the erotic (and esp. the strangely erotic) being dirty and confined to some backroom - you can find the above picture reporduced as netsuke (a miniature sculpture originally a toggle for one's purse or to stop items from slipping off your kimono cord), prints and stained glass. However these appear to be modern interpretations of the theme but there are apparently versions from the 1760-1770s and good overviews of these older pieces can be found here and here. And before people roll their eyes and say "only in Japan" they should read this article on the erotic potential of the octopus. And this piece entitled "Kracken Power! Getting Jiggity with Cephalopods" which is one woman's description of why she enjoys this kind of thing. Also the topic of (often non-consensual) bestiality isn't confined to Japan and one of the most famous versions of this theme is the legend of "Leda and the Swan" where Zeus took on the form of the swan to have his evil way with Leda. It has inspired some of the greatest artists resulting in a poem by W.B. Yeats as well as countless paintings by the likes of Cezanne, Correggio, da Vinci and Matisse (and numerous other artists). It is also a background theme in Peter Greenaway's 1985 film A Zed and Two Noughts (which is a very very strange film in itself). So drawing the various threads together I'd suggest that the reason for tentacle porn and why we in the West view it as very strange is because of the difference between animism, religions still based on the worship of nature (like Shinto), and Christianity (which rejected a lot of 'pagan' practices but incorporated others). As can be seen above pre-Christian European myths dealt openly with the blurring of the line between human and animal (even into sexual areas). Shinto, which worships numerous gods which are aspects of nature, is widespread in Japan and was once the state religion - it also has no strict rules, etc. and people can incorporate aspects of Shinto into other religions so the general ideas are even more widespread in Japan. It has to be relevant that the Edo Period (1600-1868), from which all the original pieces date from, saw an upsurge in the worship of Shinto. (information on Shinto). Although the modern resurgence in tentacle porn is a way to work around the rules of hentai it appears, to me anyway, that Japanese culture was more open to this kind of imagery.

Also the issue of cephalod reproduction comes up a lot in the world of science - in fact a posting at the Fortean Times forum pointing to this kind of thing was called Squid porn attempt which discussed BCC report on an attmept to trap squid using sex as the bait. A recent report in Nature also touched on the erections of octupi (no pun intended). See: Norman, M.D. & Lu, C.C. (1997) Sex in giant squid. Nature 389. 683 - 4. File this under 'Its a funny old world' and then try and forget all about it ;)

Links: Anime Encyclopedia's tentacle porn entry - it is allegedly also known as 'naughty tentacles'. Wikipedia entry - which I have contributed to.

Labels: Erotismo

Pulpos en el cielo -Cometa y Kraus-

Published Friday, February 25, 2005 by Spyder.

Acabo de descubrir el blog Seguro Azar de esos que me encantaría haber leido con calma y tiempo, y resulta que cuando uno lo descubre él blog ya está muerto. Pero bueno, como en los naufragios uno siempre puede asistir a la playa para ver los restos.

Esta es una de sus entradas...

Cuidado Alfredo, un pulpo

- ¡Cuidado Alfredo! ¡Un pulpo!.

- ¿Dónde, dónde?

- No, por ahí no, detrás.

¡Está volando!

[Alfredo Kraus en el festival de cometas de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria hace unas semanas]

Esta es una de sus entradas...

Cuidado Alfredo, un pulpo

- ¡Cuidado Alfredo! ¡Un pulpo!.

- ¿Dónde, dónde?

- No, por ahí no, detrás.

¡Está volando!

[Alfredo Kraus en el festival de cometas de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria hace unas semanas]

Labels: Camisetas, Monstruos marinos, Pulpos celestes

Arte y pulpos -Laura Walker Scott-

Published Thursday, February 24, 2005 by Spyder.

El cuadro es de Laura Walker Scott, que como ella explica está empezando en esto de la pintura.

"I would like the viewer to feel and decide what a particular piece means to them.

I started drawing in 2005. I have no formal training and I think that helps me not worry about rules. Drawing has quickly and surprisingly become a means for a dive into my spirituality: For me, creating something is a prayer and an exercise in discipline. Letting something be created is an exercise in surrender and faith and hope. Letting it go reminds me that everything is transient.

I love color and vacillate between simplicity and complication in my themes. My projects usually start with the need to see certain colors and then the subject matter follows. Pastels are my favorite medium because they allow me to be spontaneous, not worry about "mistakes" which can be easily corrected, and achieve instant, satisfying results. I am satisfied with a piece when the colors dazzle my eyes and the composition is calming and harmonious.

Once, I complete a piece, like a cheetah cub being pushed out of the den, it lives on it's own. And in it's life, if all goes well, it may make people feel something, or remind them of a time, or place, or dream. It may travel around or live in a stable home, or it may end up on the wall of a dive bar in the year 2082. All good.

I am currently living in Portland, Oregon".

I started drawing in 2005. I have no formal training and I think that helps me not worry about rules. Drawing has quickly and surprisingly become a means for a dive into my spirituality: For me, creating something is a prayer and an exercise in discipline. Letting something be created is an exercise in surrender and faith and hope. Letting it go reminds me that everything is transient.

I love color and vacillate between simplicity and complication in my themes. My projects usually start with the need to see certain colors and then the subject matter follows. Pastels are my favorite medium because they allow me to be spontaneous, not worry about "mistakes" which can be easily corrected, and achieve instant, satisfying results. I am satisfied with a piece when the colors dazzle my eyes and the composition is calming and harmonious.

Once, I complete a piece, like a cheetah cub being pushed out of the den, it lives on it's own. And in it's life, if all goes well, it may make people feel something, or remind them of a time, or place, or dream. It may travel around or live in a stable home, or it may end up on the wall of a dive bar in the year 2082. All good.

I am currently living in Portland, Oregon".

Labels: Artistas

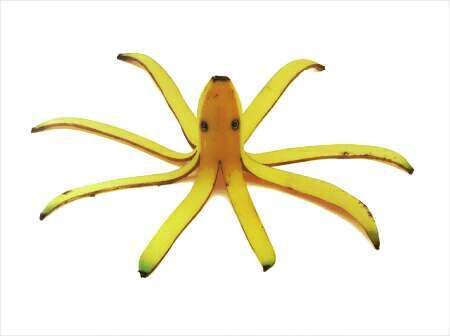

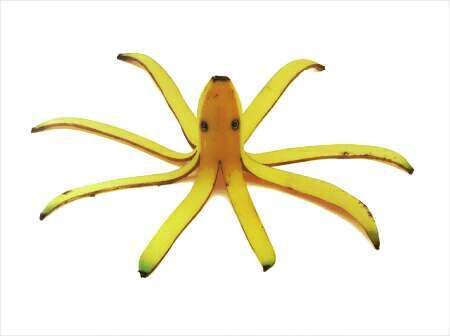

Banana Octopus

Published Wednesday, February 23, 2005 by Spyder.

Y más fácil aún, ¿quiere hacer un pulpo amarillo? Pues bien busque un plátano, pélelo con cuidado y siga el modelo...

Y aunque parezca algo cómico, el negocio es el negocio.

Home Grown: Banana Octopus Figurine

Sale Price: $8.47

Product Description

These veggie critters are a welcome addition to kitchens across the country and are cleverly posed to keep us giggling. Stone resin.

Product Dimension

L: 5.50" x W: 2.70" x H: 4.70" (13.97 cm x 6.86 cm x 11.94 cm)

Y aunque parezca algo cómico, el negocio es el negocio.

Home Grown: Banana Octopus Figurine

Sale Price: $8.47

Product Description

These veggie critters are a welcome addition to kitchens across the country and are cleverly posed to keep us giggling. Stone resin.

Product Dimension

L: 5.50" x W: 2.70" x H: 4.70" (13.97 cm x 6.86 cm x 11.94 cm)

Labels: Juegos

Actividades infantiles con pulpos.

Published Tuesday, February 22, 2005 by Spyder.

Actividad para los más pequeños:

Dificultad mínima (Sólo saber inglés y casi ni eso...).

Por si alguien no lo ve claro, se coge rollo de papel de water, se pinta y se colocan unos retales de papel con forma de tentáculos que se pegan a la estructura (ja!) inicial.

OCTOPUS CRAFT

For the octopus, you will need a toilet paper roll, a printer, something to colour with, scissors, glue, and paper (I prefer construction paper).

Print out the template of choice.

Colour (where appropriate) and cut out the template pieces.

Glue the large rectangular piece on first to cover the tube. I found a full tp roll was a bit too tall for the octopus, so cut it down a bit (use the height of the rectangle as a guide).

bend about 1/4 inch of each tentacle and glue to the inside of the tube.

Younger children can count the tentacles (8).

Slightly older children can count the suckers on each tentacle (4) and the tentacles (8) and then sort out that 4 x 8 = 32 either by multiplying or by counting all the suckers.

Dificultad mínima (Sólo saber inglés y casi ni eso...).

Por si alguien no lo ve claro, se coge rollo de papel de water, se pinta y se colocan unos retales de papel con forma de tentáculos que se pegan a la estructura (ja!) inicial.

OCTOPUS CRAFT

For the octopus, you will need a toilet paper roll, a printer, something to colour with, scissors, glue, and paper (I prefer construction paper).

Print out the template of choice.

Colour (where appropriate) and cut out the template pieces.

Glue the large rectangular piece on first to cover the tube. I found a full tp roll was a bit too tall for the octopus, so cut it down a bit (use the height of the rectangle as a guide).

bend about 1/4 inch of each tentacle and glue to the inside of the tube.

Younger children can count the tentacles (8).

Slightly older children can count the suckers on each tentacle (4) and the tentacles (8) and then sort out that 4 x 8 = 32 either by multiplying or by counting all the suckers.

Labels: Juegos

Fotografías de pulpos -Publicidad hasta en la sopa-

Published Sunday, February 20, 2005 by Spyder.

Enviada por Topp

Beba Cocacola...

(Ni pagando a la mejor agencia publicitaria Cocacola obtendría una imagen así).

Wet Pixel es posiblemente la mejor web de fotografía submarina, es una web de estas que premian la mejor foto semanal o mensual, y el nivel de los fotógrafos es bastante alto. Esta es una de las ganadoras.

Labels: Fotografías

Pulpos -Entrevista a Mark Norman- Octopus Man-

Published Friday, February 18, 2005 by Spyder.Mark Norman es un biólogo marino considerado como uno de los mayores expertos en cefalópodos. Trabaja para la Universidad de Melbourne (Australia) y lleva más de una década filmando y escribiendo exclusivamente sobre el mundo de los cefalópodos. En sus inmersiones ha descubierto más de 100 especies de pulpos.

Su libro más conocido es Cephalopods: A World Guide, un libro publicado en el 2000 y que contiene más de 800 fortografías en color de cefalópodos en su habitat natural.

Reproduzco la entrevista que mantiene la periodista Jonica Newby con Mark Norman para un documental

Octopus Man

Via la cadena americana ABC

Reporter: Jonica Newby

Producer: Paul Faint

21 March 2002

Science fiction buffs have come up with many strange depictions of alien life, but imagine a creature with a beak like a parrot, no bones in its body, swallows its food through the hole in the centre of its doughnut shaped brain, has three hearts, blue blood, skin that can change colours like a television screen, eight arms growing out of its lips, moves by jet propulsion and can transform its body shape to mimic other life forms. This is no science fiction. It's known as a Cephalopod, or more commonly, an Octopus.

Scientist, author and film-maker, Mark Norman is one of the world's leading experts on octopus, squid, and cuttlefish (Cephalopods) and he takes us night diving in Melbourne's Port Phillip Bay looking for these alien creatures. In this eerie underwater world we discover their strange and elusive behaviours, why they are so rarely seen and why, until recently, we knew so little about them. We examine the body of a Giant Squid, a mythical creature that has never been seen alive in its natural habitat, over a kilometre below the surface of the ocean. And, we put this dedicated scientist and lover of Cephalopods to the ultimate test. Will he eat calamari rings?

Narration: We’re on the outskirts of Melbourne. There’ve been reports that alien life forms have been spotted right at the end of this pier and apparently they only come out at night. Now these scientists know what to expect, they’ve seen these kind of things before. They’re pretty sure what we’re dealing with are Cephalopods. So, do you think they’re down there?...That’s what we’re here to find out. Dr Mark Norman has dedicated his adult life to hunting Cephalopods…. And no… They are not from out of space.

But there is something very science fiction about descending into the icy black waters of Port Phillip Bay in search of the strangest creatures on earth. They’re the ultimate ‘Masters of Disguise’… Almost impossible to find. And as Mark tells it they are so different in design they might as well be aliens.

Mark Norman: You couldn’t get an animal that’s sort of more different or more alien to us. They’ve got such a weird shape to start with. Like they’ve got eight arms coming off their mouth. When they walk around it’s like they’re running round on super lips. They’ve got a head in the middle of their body. They’ve got a doughnut shaped brain. They’ve got three hearts. Blue blood. Jet propulsion. A bag out the back like a beanbag that they stick all the body bits in.

Narration: The Cephalopods include octopus, cuttlefish and squid. This one’s a Southern Sand Octopus. Apart from eating them with fish and chips, most of us know very little about them.

Mark Norman: And I bet most people around here, I mean this is almost the suburbs, they wouldn’t even know these animals are here. I think they’re kind of the ‘monsters of the deep’ …and most people wouldn’t even stick their head under water at night let alone poke around far out in the bay. There are just such amazing creatures out there.

Narration: By diving at night Mark has been able to identify and film the behaviour of these mainly nocturnal animals. One of his particular favourites is the aptly named…Dumpling Squid. He’s not much to look at, but this little guy’s got a few tricks up his tentacles.

Mark Norman: Well one of them is that they can glue sand on the back of their body and have it as camouflage when they’re swimming around during the day. They have special glue glands in their skin and if they get attacked they’ve also got acid glands in the skin and they can squirt acid and that disconnects the glue and the sand coat and they can drop that as a decoy while they swim off in another direction. So they sort of have their own glue and their own anti-glue built into their skin above these nasties that are waiting to chomp any passing shadow.

Jonica Newby: Tell me. Night dives, men in black, do you ever feel like you’re living in an episode of the X Files?

Mark Norman: No. Most of the time we’re sitting going what the hell are we doing here it’s four in the morning, it’s eight degrees in the air, it’s two degrees in the water. We wish we were at home watching the X Files.

Narration: I’m still not convinced. Especially when Mark takes me to his work the next day at the Melbourne Museum. Row upon row of weird life forms preserved in glass jars. They give little indication as to the disguise strategies these animals have when they are alive.

Mark Norman: Well this one is called the day octopus and it’s rare for an octopus to be walking around during daytime and this guy does it because he’s so good at camouflage and so he doesn’t look much while he’s dead, he’s sort of just a big gooby bit of rubber or chewing gum, but when they’re alive the skin of these animals is spectacular. It can do colour changes all the time. It can also do shape changes where it sticks up all these spikes on the body. It can look like seaweeds, can look like rocks, can look like coral and so it’s almost like their skin’s covered in television screens for colour change and then add the shape change on top of it. It makes animation graphics in movies look like paint drying.

Narration: And isn’t he the reason why you nearly didn’t get your Phd?

Mark Norman: The start of my Phd was really bad because I spent three months on my first trip to the Great Barrier Reef looking for octopuses and in three months didn’t find a single octopus. I ended up buying one at a fishing co-op and bringing it home in the boot of my little rusty car thinking my life was over and it wasn’t till the second trip …that I started getting an eye in and getting a feel for the shape of the animals…and what you look for is not a shape because the shape looks like a rock or a coral, you look for a slow movement or a kind of gradual shift in colour out of the corner of your eyes often. And in the early trips I was probably kicking them in the head on a regular basis.

Narration: Since this less than spectacular start Dr Norman has discovered a previously unknown galaxy of cephalopods. He has single-handedly identified over 150 new species. But none so extraordinary as the never before filmed Mimic Octopus.

Mark Norman: Well the mimic octopus is an interesting animal because it takes it one step further. Instead of matching a background like camouflage it actually becomes an object or an animal in its own right and the place that it lives is bare sand flats and mud flats out in shallow waters of Indonesia and New Guinea. And so being caught in the open by a passing fish you’ve got to look either deadly or inedible and this octopus has developed this repertoire of looking like a flounder, poisonous flounder, poisonous lion fish, a poisonous sea snake. It just is able to do all these weird postures and weird behaviours. So in the case of the sea snake if it gets hassled by certain sorts of attackers and it’s often little aggressive damsel fish it will put six arms down a hole, put the other two up and undulate them like the kind of striking pose of a banded sea snake which are very poisonous and are found in the area. So evolution has sort of led to this amazing octopus behaviour where it’s wandering round copying all these things that live in the same area.

Narration: Why do they need such incredibly diverse strategies?

Mark Norman: Well I think the reason that this group’s ended up with such weird forms, high speed, mega camouflage, all these different sorts of behaviours is because they are a really good meal. You don’t have bones. You don’t have armour. You don’t have poisons. You don’t have spines. And so these critters are really rump steak swimming around and so they have to be faster or cleverer or better at squeezing through tiny holes or really good at hiding or conning animals that they are a poisonous sea snake. And so I think the pressure to out evolve their fish predators has led to this amazing group of animals.

Narration: And perhaps the most amazing of all is the legendary giant squid. No one has ever seen one alive. Only these specimens dragged up in fishing nets betray its existence. It has adopted the ultimate defence, hiding deep in the ocean, beyond the reach even of light.

It lives down in these cold black waters acting as an ambush predator shooting out and grabbing passing fish and squid. I love the idea we know so little about it. It’s never been seen live in its natural environment….. It’s actually a good figurehead for how little we know about the deep sea in general and we know very little. We’ve covered less than 1% of the deep ocean floor and yet if people came from outer space and said what is your most common habitat on earth it would be the deep sea and we know more about what’s under rocks on Mars than we do about what’s in our own deep ocean.

Mark Norman: So this will give you an idea of how big giant squids really are. These are the two feeding tentacles out of a 10 metre long giant squid. So these are the tentacles they shoot out to grab their food with. So this is how they grab the squid and the fish that they eat.

Narration: So how big do these things grow?

Mark Norman: Well this one’s about 10 metres long and the biggest on record is 18 metres so the length of a bus.

Narration: They’re just amazing! But still it’s a hell of a lot of calamari.

Mark Norman: It’s a hell of a lot of calamari and the rings would have been the size of car tyres...

Narration: Alright, the acid test. Can I tempt you?

Mark Norman: Calamari. Yes you can.

Narration: I can’t believe it. I mean after everything you know about how intelligent they are and how versatile how can you actually eat them?

Mark Norman: Compared with all the other seafood that’s out there they’re probably one of the better ones to eat. They grow fast. They’re short lived. They reproduce really well. Compare that with prawns or deep sea fish I’d much rather eat this if I don’t think about it too hard.

Narration: Prove it. Cheers.

Mmmm.

Labels: Comportamiento

Fotografías de pulpos -La familia unida...-

Published Thursday, February 17, 2005 by Spyder.Antonio dal Masetto -Pulpo-

Published Wednesday, February 16, 2005 by Spyder.El hombre se entera que esta noche, en el Verde, hay cazuela de pulpo, así que decide no perdérsela y ahí está acodado a la barra, esperando y dispuesto a disfrutar de una buena cena ya que se trata de uno de sus platos favoritos. Aparece Romero, un carpintero del barrio. Saluda y se le sienta al lado. El hombre contesta amablemente, aunque este encuentro no lo haga feliz. Pensaba comer en paz y sabe que Romero tiene el vicio de la comunicación, práctica que el hombre no reprueba, salvo cuando intentan experimentarla con él. Efectivamente, Romero se larga a hablar y a contarle de su vida. Está realizando un trabajo importante, en la casa de una turca, viuda, que vive con tres hijas cuyas edades oscilan entre los veinte y los treinta años.

Mientras escucha, el hombre advierte que alguien se ha sentado del otro lado, a su izquierda. Reconoce a Pierre Fontenelle, el Exorcista. Lo ha visto una sola vez, pero es inconfundible con su sobretodo negro y la polera blanca en la noche calurosa. El hombre se pregunta si volverá a repetir la ceremonia de la hostia.

Romero, mientras tanto, sigue con su historia: teniendo en cuenta que el trabajo encomendado se prolongará bastante tiempo y que él vive solo, un mediodía la turca mayor le propone que ocupe momentáneamente una piecita en la terraza de la casa. Romero acepta. Por lo tanto se muda, trabaja, almuerza y cena con las mujeres. Una noche, tarde, se abre la puerta de la pieza donde duerme y en la claridad lunar advierte que está recibiendo la visita de la turca mayor. Tienen un encuentro muy acalorado, después la turca se va y sigue la rutina de siempre.

A la noche siguiente, vuelve a abrirse la puerta. Romero piensa que se trata nuevamente de la turca mayor, pero esta vez la que acude es una de las turquitas. Posteriormente aparece la segunda turquita y luego la tercera. Durante el día nadie habla del asunto y es como si se tratara de un gran secreto. Romero trabaja duro, se alimenta bien, se acuesta y espera.

El hombre oye, a su izquierda, la voz del Exorcista que recita: "La amada se desliza a través de la noche con andar de gacela y sus labios son dulces como el néctar de las flores". Aclara: "Cantar de los Cantares."

Pide perdón por la interrupción, estira la mano por delante del hombre y se presenta a Romero: "Pierre Fontenelle." Inmediatamente pregunta si las cuatro mujeres son lindas. Romero contesta que son ardientes y que según su modesta opinión, en cuanto a mujeres fogosas, no hay nada que supere a una turca fogosa, no importa la edad que tenga. El hombre percibe que hacia la izquierda, por el lado del Exorcista, acaba de aumentar considerablemente la temperatura ambiente. Por fin llega la cazuela.

Apresado entre dos fuegos, el hombre se resigna y empieza a comer. De pronto advierte que el Exorcista extrae una hostia del bolsillo, la sostiene en la mano y la aprieta un poco con el pulgar en la parte superior, de manera que se ahueque y tome forma de cuchara. Después introduce la hostia en la cazuela, la maneja con habilidad y consigue llevarse un buen trozo de pulpo. Se chorrea salsa sobre la solapa del sobretodo y se limpia con una servilleta de papel. Al hombre esto no le gusta nada y está a punto de ponerse un poco maleducado. Pero recapacita y se dice que nada ni nadie conseguirá arruinarle la cena, así que se dirige al Exorcista y solamente pregunta: "¿Ya no las come con vinagre?" "Según la hora", contesta Pierre Fontenelle.

Mientras tanto, Romero sigue con su historia y confiesa que si bien la situación con las turcas le agrada, está comenzando a sentirse un poco raro, como si se encontrase apresado en una tela de araña y se lo estuviesen devorando lentamente. El Exorcista vuelve a interrumpirlo y, disculpándose, opina que en esa casa reina una enorme confusión, un gran extravío y que esas mujeres, sin duda, necesitan un guía espiritual. Por lo tanto se ofrece para efectuar una visita desinteresada a las turcas, esa misma noche si Romero lo desea. Ahí nomás le pide la dirección. Romero se hace el tonto y no contesta. El Exorcista declama: "Si entras en casa de mujer sola y esa mujer se enseñorea sobre tu cuerpo y espíritu, no deseches la ayuda del hombre sabio. Agustín, Confesiones." Vuelve a pedir la dirección de las turcas y Romero sigue haciéndose el distraído.

El hombre, de reojo, ve que en la mano del Exorcista acaba de aparecer una cosa blanca y redonda que pretende avanzar hacia el pulpo. Entonces toma rápidamente la cazuela y se muda a una mesa. Automáticamente, el Exorcista y Romero se sientan con él. El hombre se corre hasta quedar arrinconado contra la pared. Protege la cazuela con la mano izquierda, mientras come con la derecha.

El Exorcista insiste: "Cuando tropieces con cuatro mujeres y adviertas que sus almas están muy confundidas, acude inmediatamente a un hombre del Señor, porque él, sólo él y únicamente él podrá aportar ayuda a las extraviadas hijas del Levante. Pablo, Epístola a los Corintios."

Romero sigue sin largar prenda. El hombre, siempre en la posición de defender su pulpo, oye la última frase de Pierre Fontenelle y se dice que esa carta, seguramente, los Corintios no la recibieron nunca.

Antonio Dal Masetto nació en Intra, Italia, en 1938, de padres campesinos, Narciso y María. Después de la Segunda Guerra, en 1950, emigró a la Argentina. Se radicó en Salto con su familia y aprendió el castellano leyendo libros que elegía al azar en la biblioteca del pueblo. "Sufrí mucho con el traslado. Me sentía un marciano en el mundo", dice Dal Masetto de sus comienzos en el nuevo país. El tema de la inmigración está presente en sus libros, como en las novelas Oscuramente fuerte es la vida y La tierra incomparable. A los 18 años llegó a Buenos Aires. En sus comienzos fue albañil, pintor, heladero, vendedor ambulante de artículos del hogar, empleado público, periodista y, desde los 43 años, escritor. En 1964 publicó su primer libro de cuentos, que mereció una mención en el Premio Casa de las Américas. Recibió dos veces el Segundo Premio Municipal —por Fuego a discreción y Ni perros ni gatos— y el Primer Premio Municipal por la novela Oscuramente fuerte es la vida. Su libro Siempre es difícil volver a casa fue traducido al francés y llevado al cine por Jorge Polaco. Su novela La tierra incomparable, recibió el Premio Planeta Biblioteca del Sur 1994. Es un asiduo colaborador del periódico Página/12 de Buenos Aires.

Labels: Literatura

Sombrero pulpero -La vida es de color rosa-

Published Tuesday, February 15, 2005 by Spyder.

¿No se decidieron ayer? Pues si queda de P... M.. colocarse un pulpo rosa en la cabeza!!!

Dibujo de Soras Michelangelo

Imagínense la niña de ayer, un poquito már crecidita. Voilà

Grab 4 extra pair of legs in snap with this Octopus hat and mosey on down to an aquatic themed party. Made from purple cotton velveteen. Google eyes move around when you hit the dance floor and do the '10 step'. Available color: Purple. Available size: One size fits most.

En Village Hat Shop, por el módico precio de $21.95

Dibujo de Soras Michelangelo

Imagínense la niña de ayer, un poquito már crecidita. Voilà

Grab 4 extra pair of legs in snap with this Octopus hat and mosey on down to an aquatic themed party. Made from purple cotton velveteen. Google eyes move around when you hit the dance floor and do the '10 step'. Available color: Purple. Available size: One size fits most.

En Village Hat Shop, por el módico precio de $21.95

Sombrero pulpero -Party Hats-

Published Monday, February 14, 2005 by Spyder.

Imprescindible para fiestas marinas (y seguro que no pasas desapercibido...)

Comprar en Clothing and accessories.com

Arte y pulpos -Bent Adrian-

Published Saturday, February 12, 2005 by Spyder.

Los cuadros son del artista Brent Adrian, y corresponden a su serie Somata. Unos cuadros donde se representan trozos de carne o vísceras de animales muertos.

La página del artista se puede visitar aquí (El dominio es Kingjackass, cuya traducción creo que es Rey asno). La página tiene un aspecto igual de frío que sus cuadros y apenas hay datos del artista.

Pero aquí al menos dejo una referencia del artista acerca de Somata:

Somata is a selection from a body of work I have been pursuing for the past two years. The subject is an up-close exploration of the flesh of dead animals, all of which were purchased from a local grocery store. These images are of three animals- a roasted duck, an octopus (thawed and then dried) and a filleted fish. I selected these animals based on the way they looked rather than their specific identity. I am most interested in the inherent similarity of their flesh. The images are close-cropped to retain a sense of ambiguity. The lighting and space also remain ambiguous to enhance the sensuous quality of the surfaces. The paint handling is thick and visceral to emphasize the importance of the material. Often, the pieces are combined into diptychs to imply a sense of movement, the passing of time, or a transformation.

Essentially, all living things are made of flesh and are bound in the same inevitable cycle. My interest in the sensory experience of cutting into dead animals is a result of struggling with my own mortality and an upbringing that devalued the flesh in favor of something greater. I believe the flesh itself can become something more if it is treated with reverence. It has been my goal to create paintings that pay homage to this beautiful physicality.

Labels: Artistas

Cocina -Ensalada de acelgas, pulpo y gulas-

Published Friday, February 11, 2005 by Spyder.

Ingredientes:

• pulpo cocido, 1 pata

• gulas, 25 gramos

• acelgas,

• cebolla,

• ajo, 2 dientes

• guindilla roja,

• albahaca fresca,

• canela,

• vinagre balsámico,

• pimienta blanca,

• aceite,

• sal, al gusto

Elaboración

Fuente: Accua.com

• pulpo cocido, 1 pata

• gulas, 25 gramos

• acelgas,

• cebolla,

• ajo, 2 dientes

• guindilla roja,

• albahaca fresca,

• canela,

• vinagre balsámico,

• pimienta blanca,

• aceite,

• sal, al gusto

Elaboración

Cogemos seis hojas de acelgas y le quitamos las fibras. Se lavan, se pican y se reservan. Picamos muy fino media cebolla y un diente de ajo, se rehoga y se añaden las acelgas. Cubrimos con un poco de agua, añadimos una pizca de canela y dejamos que se consuma el agua. Las gulas se fríen durante un minuto con el otro diente de ajo picado y la guindilla.

Para elaborar la vinagreta picamos un par de hojas de albahaca y mezclamos la pimienta, el aceite y el vinagre. Se echa sal al gusto. El pulpo, ya cocido y troceado, se calienta un poco hasta dejarlo tibio. Cogemos un molde con forma de aro e incorporamos, por este orden, las acelgas, el pulpo, las gulas y, sobre todos los ingredientes, la vinagreta. Quitamos el aro y decoramos el plato con unas gotas de vinagreta y alabahaca picada.

Para elaborar la vinagreta picamos un par de hojas de albahaca y mezclamos la pimienta, el aceite y el vinagre. Se echa sal al gusto. El pulpo, ya cocido y troceado, se calienta un poco hasta dejarlo tibio. Cogemos un molde con forma de aro e incorporamos, por este orden, las acelgas, el pulpo, las gulas y, sobre todos los ingredientes, la vinagreta. Quitamos el aro y decoramos el plato con unas gotas de vinagreta y alabahaca picada.

Fuente: Accua.com

Labels: Gastronomía

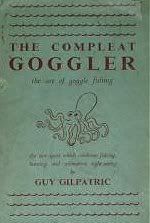

Pulpos y literatura -Guy Gilpatric-

Published Thursday, February 10, 2005 by Spyder.En los años veinte el escritor norteamerican Guy Gilpatric (1896-1950) fue uno de los pioneros sobre la escritura de la pesca submarina. Mientras que su trabajo por la mañana consistía en escribir sus novelas y crónicas para el Saturday Evening, por la tarde se dedicaba a la pesca submarina. En 1.929, Gilpatric impermeabilizó unas gafas de aviador, que le permitieron ver bien por primera vez el fondo marino. No tardó en hacer prosélitos entre los amigos que le rodeaban.

La muerte de Gilpatric tiene un aire trágico, murió suicidándose después de matar a su mujer, enferma terminal.

Gilpatric publicó en 1938 el primer libro que trató sobre la pesca submarina en su modalidad deportiva: The Compleat Googler, que si mi intuición es correcta debe significar algo así como La búsqueda Completa (se admiten traducciones mejores… pero es que los términos “Compleat” y “Googler” no me resultan demasiado familiares…

THE COMPLEAT GOGGLER

Guy Gilpatric.

First edition 1938. Dodd, Mead and Company.

Second edition 1957, in conjunction with Skin Diver Magazine.

Hardcover, dust jacket, 182 pages, mono prints.

The dust jacket, left, is from the 1957 edition. It is identical to the original edition except for the brief text above the author's name.

The 1938 cover text is: The new sport which combines fishing, hunting and submarine sightseeing. Note: A copy of this edition went for 1805 English pounds = approx $300 US dollars = approx $550 Australian dollars on eBay, March 2003.

Vía Classic Dive Books

"I must admit to certain sadness when I read of so many fish being killed in the name of sport, but The Compleat Goggler provides an impression that the author has compassion for the food that he kills. He certainly developed an understanding of the ways of the various fish species. The hunting of the huge merou unflatteringly named Bonehead is not a classic in the sense of Melville's Moby Dick, but it does have its moments of compassion.

And like so many early books on the animals of the sea, the octopus comes in for more than its share of derision - "... he is a rude swashbuckling lout with a nasty disposition, prodigious strength and defective, if any, mentality". Not so Mr Gilpatric, but if that is your observation at the time then so be it. "His eyes, which are extremely keen, are malevolent, gold-rimmed and lumpily-protruding, being mounted in what naval architects would describe as sponsons. His mouth, a small hole located on the underside of him exactly where a mouth has no business to be, is provided with a sharp hooked beak like a parrot's. ... it is the only really hard substance in all his squashy, slimy make-up". I'd take offence at that if I was an octopus. Why must they be regarded as grotesque simply because they are different to most other marine animals. I tend to like them even if Mr Gilpatric doesn't. But Gilpatric takes several pages to quote other ‘authorities' on these ‘horrible creatures'. "If a diver is attacked by one of these creatures it is only by superhuman efforts that he can free himself from its terrible grasp". Gilpatric hunts one down over several chapters, giving it the unimaginative name of Five Fathom Kid, but turns him loose. Compassion? Perhaps".

The 1938 cover text is: The new sport which combines fishing, hunting and submarine sightseeing. Note: A copy of this edition went for 1805 English pounds = approx $300 US dollars = approx $550 Australian dollars on eBay, March 2003.

Vía Classic Dive Books

"I must admit to certain sadness when I read of so many fish being killed in the name of sport, but The Compleat Goggler provides an impression that the author has compassion for the food that he kills. He certainly developed an understanding of the ways of the various fish species. The hunting of the huge merou unflatteringly named Bonehead is not a classic in the sense of Melville's Moby Dick, but it does have its moments of compassion.

And like so many early books on the animals of the sea, the octopus comes in for more than its share of derision - "... he is a rude swashbuckling lout with a nasty disposition, prodigious strength and defective, if any, mentality". Not so Mr Gilpatric, but if that is your observation at the time then so be it. "His eyes, which are extremely keen, are malevolent, gold-rimmed and lumpily-protruding, being mounted in what naval architects would describe as sponsons. His mouth, a small hole located on the underside of him exactly where a mouth has no business to be, is provided with a sharp hooked beak like a parrot's. ... it is the only really hard substance in all his squashy, slimy make-up". I'd take offence at that if I was an octopus. Why must they be regarded as grotesque simply because they are different to most other marine animals. I tend to like them even if Mr Gilpatric doesn't. But Gilpatric takes several pages to quote other ‘authorities' on these ‘horrible creatures'. "If a diver is attacked by one of these creatures it is only by superhuman efforts that he can free himself from its terrible grasp". Gilpatric hunts one down over several chapters, giving it the unimaginative name of Five Fathom Kid, but turns him loose. Compassion? Perhaps".

Labels: Literatura

Erotismo con pulpos -Niklas Jansson- Flying Spaghetti Monster-

Published Monday, February 07, 2005 by Spyder.

Una nueva versión del cuadro de Hokusai muy divertida hecha por el artista Niklas Jansson que pinta al famoso Flying Spaghetti Monster.

El Monstruo del Spaguetti Volante viene por una disputa que se creó cuando la administración Bush implantó el creacionismo en algunas escuelas en contra de la teoría admitida por la comunidad científica del evolucionismo. Un físico llamado Bobby Henderson en tono irónico y como manera de protesta se declaró profeta de un nuevo Dios Spaguetti y fundó la iglesia del pastafarismo. Ese Dios Spaguetti tuvo eco en la obra de muchos artistas, así que de Flying Spaghetti Monster tuvo sus apariciones en distintas ciudades.

I am writing you with much concern after having read of your hearing todecide whether the alternative theory of Intelligent Design should be taughtalong with the theory of Evolution. I think we can all agree that it isimportant for students to hear multiple viewpoints so they can choose forthemselves the theory that makes the most sense to them. I am concerned,however, that students will only hear one theory of Intelligent Design.Let us remember that there are multiple theories of Intelligent Design. Iand many others around the world are of the strong belief that the universe wascreated by a Flying Spaghetti Monster.

El Monstruo del Spaguetti Volante viene por una disputa que se creó cuando la administración Bush implantó el creacionismo en algunas escuelas en contra de la teoría admitida por la comunidad científica del evolucionismo. Un físico llamado Bobby Henderson en tono irónico y como manera de protesta se declaró profeta de un nuevo Dios Spaguetti y fundó la iglesia del pastafarismo. Ese Dios Spaguetti tuvo eco en la obra de muchos artistas, así que de Flying Spaghetti Monster tuvo sus apariciones en distintas ciudades.

I am writing you with much concern after having read of your hearing todecide whether the alternative theory of Intelligent Design should be taughtalong with the theory of Evolution. I think we can all agree that it isimportant for students to hear multiple viewpoints so they can choose forthemselves the theory that makes the most sense to them. I am concerned,however, that students will only hear one theory of Intelligent Design.Let us remember that there are multiple theories of Intelligent Design. Iand many others around the world are of the strong belief that the universe wascreated by a Flying Spaghetti Monster.

Labels: Erotismo

Erotismo con pulpos -David Laity-

Published Sunday, February 06, 2005 by Spyder.La versión que hizo el artista australiano David Laity del cuadro de Hokusai El sueño de la esposa del pescador que tituló Bailando con Katsushika Hokusai.

Via Metro 5 Gallery

"Dream of the Fisherman's Wife is adapted from an early Japanese woodcut titled Dancing With Katsushika Hokusai. The original woodcut, smaller than A4 was printed over 200 years ago.

Dream of the Fisherman's Wife departs from the flirty, sensual imagery evident in David's other paintings, and moves into confronting erotic mythology."I have been aware of this image for years and loved it. I always thought that life-size it would be so powerful. In the mode of Pop Art I wanted to re-make this image in my style.

"I love that this image brings the historic tradition of sexually explicit art into contemporary Australian life, bridging a tradition of erotic painting across centuries and cultures.

"It's a wonderful wild image."

"I love that this image brings the historic tradition of sexually explicit art into contemporary Australian life, bridging a tradition of erotic painting across centuries and cultures.

"It's a wonderful wild image."

Labels: Erotismo

Erotismo con pulpos -Katsushika Hokusai- El sueño de la esposa del pescador

Published Saturday, February 05, 2005 by Spyder.Katsushika Hokusai, nació en Tokio, Japón, en 1760, en el período conocido como la época de Edo, y produjo bellísimos grabados y pinturas, en los que retrata la naturaleza en todo su esplendor.

Son famosas sus obras sobre el Monte Fuji, así como los grabados con temas marinos, en los que figuran frágiles barcos azotados por gigantescas olas, que parecen cobrar vida ante los ojos de los espectadores.

Son famosas sus obras sobre el Monte Fuji, así como los grabados con temas marinos, en los que figuran frágiles barcos azotados por gigantescas olas, que parecen cobrar vida ante los ojos de los espectadores.

Hokusai cuando pinta El sueño de la esposa del pescador se convierte en un referente dentro del erotismo pulpero. El grabado representa a una mujer manteniendo sexo con dos pulpos y es uno de los ukiyo-e (pinturas del mundo flotante) más reconocidos. David Laity rehizo el ukiyo-e de El sueño de la esposa del pescador en una pintura con el mismo nombre, y Masami Teraoka actualizó la imagen con su trabajo en el 2001 "Sarah and Octopus/Séptimo Cielo", parte de su colección Olas y Plagas.

The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife is an erotic woodcut made circa 1820 by Hokusai, perhaps the first instance of tentacle porn. It features a woman entwined sexually with a pair of octopuses. She is kissing a small octopus, while a larger one is performing cunnilingus on her. This ukiyo-e woodcut arose in the Edo period in Japan when Shinto was making a resurgence and the resulting Animism and a more playful attitude to sexuality combined powerfully in Hokusai's piece. It is a celebrated example of shunga and has been reworked by a number of artists including:

David Laity reworked the woodcut into a painting of the same name. He claims that the original piece was actually titled "Dancing With Katsushika Hokusai".

Masami Teraoka brought the image up to date with his 2001 work "Sarah and Octopus/Seventh Heaven part of his "Waves and Plagues" collection.

A parody image featuring the Flying Spaghetti Monster has been created by artist Niklas Jansson.

British artist Lali Chetwynd included a reenactment of the woodcut as part of her performance of "Erotics and Beastiality: Depraved Creativity" at the Liverpool Biennial of 2004. The scene saw bikini clad artist Eva Stenram disappear legs first into the costume of the slowly gyrating animal, operated by writer Tom McCarthy.

David Laity reworked the woodcut into a painting of the same name. He claims that the original piece was actually titled "Dancing With Katsushika Hokusai".

Masami Teraoka brought the image up to date with his 2001 work "Sarah and Octopus/Seventh Heaven part of his "Waves and Plagues" collection.

A parody image featuring the Flying Spaghetti Monster has been created by artist Niklas Jansson.

British artist Lali Chetwynd included a reenactment of the woodcut as part of her performance of "Erotics and Beastiality: Depraved Creativity" at the Liverpool Biennial of 2004. The scene saw bikini clad artist Eva Stenram disappear legs first into the costume of the slowly gyrating animal, operated by writer Tom McCarthy.

The anime series Samurai Champloo made playful reference to this image in episode 5, "Artistic Anarchy". Mugen, looking through a ukiyo-e artist's collection, comments "Whoa, doin' it with a squid". The series is set in roughly 1675, well before the creation of this image, but anachronism is one of the hallmarks of Champloo.

The collection of the comic book Commies from Mars: The Red Planet has a parody image as part of the general mayhem of Martians taking over the Earth. Artwork by John Pound.

Similar themes of human females having sexual intercourse with sea life have been displayed since the 17th century in Japanese netsuke, small carved sculptures only a few inches in height and often extremely elaborate. Once, people walked the streets of Edo with their moneypurses hanging from their belts, netsuke-pulls of human-marine erotica dangling from their drawstrings.

The collection of the comic book Commies from Mars: The Red Planet has a parody image as part of the general mayhem of Martians taking over the Earth. Artwork by John Pound.

Similar themes of human females having sexual intercourse with sea life have been displayed since the 17th century in Japanese netsuke, small carved sculptures only a few inches in height and often extremely elaborate. Once, people walked the streets of Edo with their moneypurses hanging from their belts, netsuke-pulls of human-marine erotica dangling from their drawstrings.

Labels: Erotismo

Pulpos y películas -Octaman-

Published Friday, February 04, 2005 by Spyder.

Octaman

GENERO: Terror

PAIS: E.E.U.U.

DURACION: 76 Min

AÑO: 1971

DIRECTOR: Harry Essex

GUION: Harry Essex y Leigh Chapman

INTERPRETES: Jeff Morrow, Kerwin Mathews, Pier Angeli y Wally Rose

PRODUCTOR: Michael Kreike

FOTOGRAFÍA: Robert Caramico

Kerwin Matthews es un científico que está analizando la contaminación radiactiva de algunos lagos de México. El y otros compañeros descubrirán unos pulpos con aspecto gomoso, que parecen presentar una inteligencia más allá de lo normal. Después de haber atrapado algunos y de llevarlos a la Universidad más cercana para estudiarlos, aparecerá Octoman, un ser que parece una mezcla abobinable de persona y pulpo. A partir de entonces el Octoman aterrorizará al pueblo más cercano, hasta que finalmente será vencido.

La película no debe ser demasiado buena, porque apenas hay referencias en la red sobre ella y las que hay son más bien negativas. Hay un crítica bastante amplia sobre ella en la página “The bad movie report”, lo cual ya indica lo que uno puede esperar de ella; para el crítico visionarla ocasiona ochenta minutos de sufrimiento.

Remarcar que los pobres efectos especiales tienen como culpable a Rick Baker, responsable especialmente del inexpresivo traje de latex de Octoman.

También es interesante algunas característica que presenta Octoman, que por ejemplo parece tener un extraño poder psíquico que inmoviliza a las víctimas, a las que después abofetea con sus tentáculos. Y también destacar la curiosa visión de Octoman, que nada tiene que ver con los desarrollados ojos de un pulpo, sino que más bien parece la visión que tendría un insecto.

Por otro lado según leo, al final de la película brillan unos ojos en la oscuridad, por lo que se supone que el director aún tenía esperanzas en roda una segunda parte que hubiera sido galardonada sin duda con más de un óscar de chocolate.

Labels: Cine

Cocina -Pulpos a la marinera-

Published Thursday, February 03, 2005 by Spyder.

Vía la cocina mexicana

Ingredientes:

1 kg. de pulpo cocido, pelado y partido

6 limones en jugo

1 cebolla grande picada

3 dientes de ajo picados

½ kg. de jitomate picado

1 manojo de perejil chino para adornar

50 grs. de alacaparras

Aceite de olivalimón rebanado para adornar

½ cucharadita de tomillo

Procedimiento:

Ponga a marinar el pulpo en el jugo de limón durante media hora.

Mezcle la cebolla con el ajo, el jitomate, las aceitunas, las alcaparras, el tomillo pulverizado, un chorro de aceite de oliva y por último el pulpo con el jugo de limón, si hace falta agregue un poco de sal.

Sirva en copas individuales y adorne con una ramita de perejil chino y una rebanada de limón.

Ingredientes:

1 kg. de pulpo cocido, pelado y partido

6 limones en jugo

1 cebolla grande picada

3 dientes de ajo picados

½ kg. de jitomate picado

1 manojo de perejil chino para adornar

50 grs. de alacaparras

Aceite de olivalimón rebanado para adornar

½ cucharadita de tomillo

Procedimiento:

Ponga a marinar el pulpo en el jugo de limón durante media hora.

Mezcle la cebolla con el ajo, el jitomate, las aceitunas, las alcaparras, el tomillo pulverizado, un chorro de aceite de oliva y por último el pulpo con el jugo de limón, si hace falta agregue un poco de sal.

Sirva en copas individuales y adorne con una ramita de perejil chino y una rebanada de limón.

Labels: Gastronomía

Pulpos utilizados para la pesca del mero

Published Wednesday, February 02, 2005 by Spyder."Los enormes meros que cazábamos eran virtualmente desconocidos en los mercados provenzales hasta que los pescadores submarinos se dedicaron a darles caza. Los pescadores profesionales los habían visto a través de cubos con fondo de cristal, pero eran incapaces de apresarlos con sus redes. Muy raramente se los habían pescado con caña. Al tragarse el anzuelo, el mero se mete en su guarida rocosa y se defiende tozudamente erizando sus espinas y apuntalándose en su agujero. Los árabes tratan de hacerlos salir colgando a un pulpo ante la entrada de la cueva y dando un tirón a tiempo, con lo que a veces se consigue pescar un mero, pero generalmente suele resultar inútil por completo. Un método muy hábil para apoderarse de un mero que haya mordido el anzuelo consiste en deslizar por el sedal un peso considerable."

J. Y. Cousteau y Frédéric Dumas –El mundo silencioso-

J. Y. Cousteau y Frédéric Dumas –El mundo silencioso-

Labels: Pesca

Erotismo con pulpos

Published Tuesday, February 01, 2005 by Spyder.Vía El mundo.es

A propósito de un grabado japonés del siglo pasado, el autor de este artículo especula sobre la sexualidad femenina a través una serie de obras de arte que guardan un punto en común

El erotismo del pulpo

ALBERTO HERNANDO

Hacia 1820 el maestro japonés Hokusai realizó un grabado que mostraba a un pulpo cuya boca está adherida al sexo de una mujer mientras sus tentáculos se introducen por su boca, sujetan uno de sus pezones y se enroscan por sus piernas y nalgas. El dibujo tiene por título El sueño de la mujer del pescador. En la escena confluyen una serie de íntimas fantasías eróticas de la mujer: la viscosidad animal, lo tentacular, lo húmedo, el horror monstruoso, el goce convulsivo y la violencia lúbrica.

El grabado de Hokusai, cuando fue conocido en los círculos artísticos occidentales, especialmente por los decadentistas, causó una gran conmoción y fue celebrado como la expresión magistral de la animalidad del deseo donde se rehabilitaba la lujuria vinculada al sufrimiento. Joris-Karl Huysmans, dirá al respecto: «¡La expresión casi sobrehumana de angustia y de dolor que convulsiona a esa larga figura de Pierrot, de nariz arqueada, y la alegría histérica que filtra al mismo tiempo de esa frente, de esos ojos cerrados de muerte, son admirables!». Otro decadentista, Felicien Rops, maestro del erotismo sacrílego y maldito, reproduciría la imagen de una manera mucho más compulsiva: una mujer desnuda se debate frente a un pulpo sujetando con cada una de sus manos fálicos tentáculos mientras que otros la penetran por la boca y la vagina y al mismo tiempo la hiere con su punzante pico.

La atracción por el tema desde la perspectiva pictórica ha perseverado hasta nuestros días: Masami Teraoka, en clave pop art y parodiando la escena de Hokusai, dibuja una mujer rubia californiana pugnando contra un pulpo cuyos tentáculos están preservados por condones (New Wave Series: Eight-Condom Fantasy): a la clave de horror erótico que conlleva la imagen del pulpo se adiciona la referencia a la amenaza de contagio letal. En relación con los condones, un aditamento de imaginación erótica y ampliación del placer son los french ticklers (cosquillas francesas) o preservativos cuya punta está provista de apéndices simulando los tentáculos de un pulpo. En esta ocasión, la forma simbólica del pulpo se reduce estratégicamente para que la posesión del cuerpo femenino sea intestina, penetre en los más hondo, frote y excite cada rincón de la vagina.

Hasta la aparición del grabado de Hokusai, la figura del pulpo velaba un discurso de lo reprimido. Simbólicamente el pulpo era asimilado al terror de los monstruos marinos (las leyendas escandinavas sobre los Kraken), señal de peligro de que algo o alguien intenta hundirte (adivinación por los posos del té); emblema de tiranía o gula extrema (Horapolo en su Hieraglyphica); o representación de un ser maligno y dañino que contrasta con el amor puro, como se evidencia en la obra de Rafael titulada Galatea, donde se expone, como exaltación del triunfo del Amor sobre el Mal, a un delfín -imagen del amor que se entrega hasta la muerte- devorando a un pulpo. Sólo Eliano, escritor griego del siglo III, en su Historia Natural habla de la incontinencia sexual del pulpo que le debilita de tal forma que constituye presa fácil para los cangrejos.

En psicología, la figura del pulpo que aparece en sueños se interpreta como complejos neuróticos que remiten a personas a las que se teme o que ejercen un dominio absorbente y tiránico; especialmente la madre castradora. En otras ocasiones, acorde con la tradición misógina freudiana, se identifica al pulpo con el miedo al sexo femenino. Por esa potencia onírica o fijación inconsciente, la imagen del pulpo en sus connotaciones eróticas ha sido un lugar común de los surrealistas. Isidore Ducasse, más conocido por Lautréamont y surrealista avant la lettre, convierte al protagonista de sus Cantos de Maldoror en un pulpo para atrapar a Dios mediante sus «Cuatrocientas ventosas bajo las axilas, hasta hacerle lanzar terribles gritos» que se convertían en «víboras» y «reptantes dotados de innumerables anillos» que «han jurado dar caza a la inocencia humana».

Dalí realizará en 1963 un dibujo dedicado a su amigo Carles Alemany titulado San Jorge luchando contra el pulpo: San Jorge se enfrenta a un pulpo enarbolando un escudo ornamentado con una cabeza de medusa. Un ojo monstruoso de largas pestañas se halla en el centro de la cabeza del pulpo; sus tentáculos están complementados por varios penes, de los cuales uno eyacula sobre el sexo de una mujer abierta de piernas. Hans Bellmer titula uno de sus grabados Cefalópodo (1968): una joven tendida muestra su sexo desde la perspectiva del culo que sirve a un tiempo para perfilar una cabeza cuya oreja se sobrepone a los repliegues de la vulva.

La poesía surrealista igualmente se hizo eco de la sugerente eroticidad del pulpo. Joyce Mansour en su obra Déchirures (1954) escribirá: «Llegan la noche y tu éxtasis/Y mi cuerpo profundo ese pulpo sin pensamiento/Engulle tu sexo agitado/Durante su nacimiento». En el poema titulado El cazador de cabezas de Michel Leiris, contenido en Haut-mal (1943), podemos leer: «La noche me abre la docilidad de sus arcanos/pero a sus pentaclos chisporreantes prefiero/el pentagrama de tu cuerpo/Cinco sentidos Cinco Tentáculos El Pulpo/hincha de sangre sus brazos pero cuánto más prefiero/la alhaja pesada de tus entrañas en la que nunca penetra la luz/a no ser el mástil deslumbrador/en el minuto en que la fauna misteriosa de un país ignorado/acude a beber en nuestra fuente/Cinco tentáculos Cinco hojas de acero».

Como fantasía tenebrosa de la mujer, Andrzej Zulawski en su filme Posesión, interpretado por Patricia Adjani, cuenta la inquietante historia de una mujer cuyo deseo crea un monstruo tentacular que la posee y destruye a todo competidor humano que se la acerque. Esa metáfora del deseo extremo ilustra la potencia de la mujer para crear sus propias realidades a partir de la fantasía.

Llegados a este punto a través de las derivaciones simbólicas del pulpo, cabe preguntarse, ¿el pulpo es una fantasía erótica específica de la mujer, o una proyección de los miedos del hombre? Ciertamente, parece lógico que es compatible con la mujer la posibilidad de fantasear sobre un ser que a un tiempo pulse y penetre todas las partes erógenas, despierte los sentidos, intensifique el placer y armonice los ritmos precisos, independientes, sincronizados, de las zonas de la carne sensibles al gozo; que dirija todas las sensaciones a una apoteosis múltiple, a un orgasmo multiplicado, a un frenesí exuberante y delirante. La mujer en ese abandono lograría a un tiempo ser objeto y usuaria de placer. Procopio en su Anécdota cuenta como la emperatriz Teodora trató de experimentar ese climax en un lance amoroso al «satisfacer completo y simultáneamente todos los orificios amorosos del cuerpo humano».

Por otro lado, el hombre, en su voracidad sexual, ha parcelado a la mujer como si fuera un territorio jalonado de agujeros a sobreponer, dominar, enchufar, insertar, acoplar... El poder sedicente del sexo masculino cree fundamentarse en esa lógica militar de ocupación. Esa obsesión por cubrir todos los orificios femeninos se manifiesta plásticamente en innúmeros dibujos que ilustran las obras libertinas del siglo XVIII donde la combinatoria de los cuerpos en la orgía muestra las diversas maneras de lograr una maximización sexual entre los componentes del grupo. Sin embargo, esa pretensión de dominio total del cuerpo femenino, esa ilusoria creencia de satisfacerla plenamente, queda desmentida por la realidad fisiológica: el breve tiempo de duración de la erección masculina denuncia su debilidad sexual y desmiente esa absurda pretensión de omnímoda potencia de satisfacción del gozo femenino. Fantasía que vela, sin duda, ese conocimiento de precariedad o descompensación respecto a la potencia orgásmica de la mujer. Miedo que asimismo, explicaría la posible y vergonzante proyección de la figura del pulpo como deseo de la mujer. Como sea, el pulpo será una sugerente metáfora más en las fronterizas relaciones entre hombres y mujeres.

Labels: Erotismo