Arte y pulpos -Gianni Candido-

Published Wednesday, May 31, 2006 by Spyder.Arte y pulpos -Giovanni Ortiz-

Published Tuesday, May 23, 2006 by Spyder.

Cocina -Ensalada de pulpos-

Published Monday, May 22, 2006 by Spyder.Ingredientes:

1 kg de pulpo

1/4 de taza de aceite

2 dientes de ajo machacados

3 ramas de perejil picado

2 cucharadas de jugo Sal y pimienta

Preparación:

Lave los pulpos y retire la bolsa de su tinta. Póngalos a hervir en agua con sal, de 20 a 40 minutos. Escúrralos y córtelos en rebanadas delgadas y colóquelos en un recipiente hondo. Prepare el aderezo poniendo en un recipiente el aceite, ajo, jugo de limón, perejil, sal y pimienta. Mezcle bien y añada esta preparación sobre los pulpos. Déjelos reposar una hora antes de servir.

Labels: Gastronomía, Recetas

Pulpo hoy, pulpo mañana

Published Sunday, May 21, 2006 by Spyder.* Departamento de Bioloxía Animal, Bioloxía Vexetal e Ecoloxía, ** Facultade de Socioloxía, Universidade da Coruña

Por Juan Freire * y Antonio García-Allut**

La actual crisis de la pesquería de pulpo en Galicia no es más que uno de los capítulos finales de una historia de sobre-explotación de nuestros recursos costeros. A lo largo de todo este siglo, se han producido situaciones similares, algunas de ellas ya sin posibilidad de solución: los colapsos de las pesquerías de ostra autóctona, langosta, boi, bogavante; la casi o total desaparición de especies como la sama, el pargo, el dentón, etc. antes presentes en nuestro litoral; o la "silenciosa" disminución de especies como el rodaballo, coruxo, pancho, santiaguiño, trancho, abadejo, etc. constituyen sólo algunos ejemplos de la reciente historia del ecosistema costero gallego. Pero, a diferencia de antaño, ahora, las opciones para elegir recursos pesqueros alternativos, son menores. En caso de un colapso o desaparición de la pesquería de pulpo, ¿hacia qué nuevo recurso orientarían los pescadores su actividad?

Hasta hace unos treinta años, los pescadores artesanales basaban su supervivencia más en una estrategia de diversificación pesquera que de especialización. Actuaban con diferentes artes sobre un rango amplio de especies que en su conjunto contribuían al sostén de sus hogares. Pero la discreta y progresiva disminución de muchas de ellas hizo que el pulpo apareciese, a partir de principios de los 80, como el recurso fundamental sobre el que se centra nuestra flota artesanal. Pocas discrepancias existen en el diagnóstico del problema. Administración y Pescadores coinciden en argumentar: a) una excesiva presión pesquera por parte de los diversos sectores de la flota y b) el incumplimiento de las normativas pesqueras, como las causas principales de la reducción y virtual colapso de numerosos stocks. Sin embargo, ambas partes se distancian en cuanto al tipo de soluciones. La Administración se empeña en incrementar el número y exigencia de las medidas técnicas de regulación. Los Pescadores, por otro lado, tachan estas medidas de inapropiadas, pues hacen cada vez más costosa, en términos económicos y de esfuerzo humano, la actividad. En la actual "crisis del pulpo", uno de los puntos a negociar entre Pescadores y Administración es el de regresar con las nasas a tierra cada fin de semana. Sin embargo, ¿qué ventajas reales supone llevar las nasas a tierra diariamente en lugar de traerlas sólo el fin de semana o dejarlas permanentemente en el mar? En teoría da la impresión de que la respuesta más beneficiosa para el porvenir del pulpo es traer las nasas a tierra con la mayor frecuencia, pero ¿quién y cómo se puede controlar el cumplimiento real de esta norma? ¿De cuantas maneras posibles se puede disimular una nasa en el mar? . O simple y llanamente: ¿qué impacto tiene para el futuro del pulpo que algunos barcos estiben diariamente unas nasas en tierra si en la práctica dejan un numero equivalente o superior en el mar? Así, estamos inmersos en un proceso de discusión continua sobre la bondad de las medidas técnicas propuestas por la Administración. Bajo nuestro punto de vista, esta discusión es totalmente estéril mientras el modelo de gestión existente, centralizado, con una Administración reguladora paternalista y un sector que se limita a cumplir (o tratar de incumplir) las regulaciones, no se modifiquen. No tiene sentido discutir sobre medidas concretas, cuando es evidente que el control de su cumplimiento es muy difícil, por no decir imposible. ¿Qué coste económico tendría la vigilancia efectiva de más de 8,000 barcos trabajando a lo largo de más de 1,300 km de litoral? Y, ¿quién debería sufragarlo?

Primero debemos asegurarnos un sistema de gestión que genere las condiciones de una aplicación efectiva (y no sólo legal) de las regulaciones, y sólo después podremos iniciar un debate técnico. Está claro que en este proceso es imprescindible contar con la participación de los pescadores. Baste mirar a nuestro alrededor. Los éxitos recientes de los planes de explotación del percebe o del marisqueo de bivalvos en nuestras costas son una consecuencia directa de la opinión y decisión de los pescadores a través de sus Cofradías en colaboración con la Administración. En otras áreas geográficas en los que se dieron problemas similares a los nuestros (y que no se encuentran precisamente en la próxima Europa, sino en países como Chile, Canadá o Australia), en donde la pesca de marisco en ecosistemas costeros tiene gran importancia, deben su éxito actual a la puesta en práctica de un nuevo modelo de gestión basado en la participación conjunta de Administración-Pescadores y en la implantación de sistemas de derechos tradicionales de uso territorial. Hoy en día, la conducta productiva de muchos pescadores en el mundo, está motivada por el deseo de incrementar sus ganancias o sus capturas en el menor tiempo posible. Algunos economistas de mediados de este siglo ya plantearon que un comportamiento guiado por esos objetivos conduciría al agotamiento de los recursos. Es decir, cuando los recursos pesqueros son explotados con un sistema de acceso abierto, el pescador busca maximizar las capturas de forma inmediata (y si es necesario, desarrollar prácticas alternativas a las limitaciones impuestas por las regulaciones), obteniendo el máximo rendimiento a corto plazo pero comprometiendo seriamente la sostenibilidad de los stocks. El pescador, como todos los humanos, es racional e inteligente, y busca, a falta de otros sistemas de organización, su éxito particular, dado que no tiene capacidad ni la oportunidad de incidir en el futuro de los recursos o de la sociedad en la que vive. Cuando ese mismo grupo de usuarios, los pescadores en nuestro caso, obtiene un derecho de explotación de los recursos, su estrategia cambia radicalmente, dado que sus objetivos individuales pasan a coincidir con los del colectivo. En estos momentos se establecen sistemas de control y gestión efectivos y poco costosos. ¿Cómo podemos desarrollar un sistema de este tipo en Galicia para la pesca artesanal? Contamos con dos grandes ventajas: a) la mayor parte de los recursos explotados por la flota artesanal tienen una fuerte estructura espacial formando stocks diferenciados y relativamente sedentarios a lo largo de la costa, y b) las flotas artesanales de las diferentes comunidades costeras han utilizado tradicionalmente áreas de pesca propias como una forma de minimizar los costes y conflictos entre vecinos. Por tanto, se podría establecer un sistema de derechos de explotación de recursos pesqueros (no de propiedad del recurso que permanecería en manos de la sociedad) otorgados a las diferentes comunidades, basados en los territorios donde históricamente han venido pescando. El papel del pescador, y en concreto el de la comunidad, pasaría a ser (y de hecho ha sucedido en el marisqueo o con el percebe) de co-gestor, junto con la Administración, y vigilante del cumplimiento de los acuerdos. La reducción de la incertidumbre que este sistema supone, permitiría una planificación a medio y largo plazo en la que la sostenibilidad biológica y económica constituirían los objetivos. Pero el cambio de modelo de gestión no significaría una dejación de las funciones de las autoridades políticas, sino una redifinición de su papel. El éxito de la co-gestión y el establecimiento de sistemas de derechos territoriales necesita de nuevos roles para políticos y técnicos, centrados en: la formación del colectivo, la participación como asesores y facilitadores en las tomas de decisiones y resolución de conflictos, etc. . Pero la historia que estamos viviendo en Galicia no es nueva. Algunos pescadores plantean la existencia de un proceso histórico cíclico en el que la sobre-explotación lleva al abandono por parte del sector de la actividad pesquera (habitualmente ligado a procesos migratorios), lo que conduce a una reducción del esfuerzo de pesca y a la futura recuperación de los stocks, lo que permite el inicio de un nuevo ciclo. Pero, la tecnología ha permitido un incremento continuado en nuestra capacidad de pesca (un mismo barco puede llevar hoy en día 10 veces más nasas que hace 10 o 20 años), y el número de pescadores ha sufrido también un incremento sostenido. Por estas razones, el nivel de sobre-explotación al que llegamos al final de cada ciclo histórico es cada vez mayor y afecta a un mayor número de recursos. Parece que, hoy en día, al contrario que en otros momentos históricos, no quedan nuevos recursos costeros para explotar. Por otra parte, la velocidad con la que se generan cambios sociales y económicos es actualmente muy superior a la de hace pocos años. ¿Qué situación socio-económica nos encontraremos dentro de unos años, tras este descanso obligado del mar? El sector artesanal sufre un proceso de envejecimiento, los jóvenes abandonan la pesca como forma de vida, por la incertidumbre económica que supone y por la existencia de alternativas más rentables y mejor valoradas socialmente. Posiblemente, dentro de unos años, no exista un colectivo heredero del actual dispuesto a reanudar la explotación de los recursos pesqueros siguiendo el presente modelo. Además, ¿qué sentido tienen las numerosas comunidades pesqueras gallegas si el rendimiento económico de la pesca se hace mínimo? Por tanto, no es difícil especular que, si en algún momento la pesca costera se volviese a mostrar rentable por la recuperación de los recursos, apareciese un nuevo estilo de explotación con un sentido más empresarial y con mayores exigencias sobre la propiedad de los recursos. Por otra parte, sin la presión de un colectivo en crisis, la Administración tendría menos problemas en otorgar dichos derechos. Este cambio de modelo de explotación podría llevar a una mejor gestión y conservación de los recursos con los beneficios económicos asociados. Pero, el papel de la pesca como factor de estructuración social y cultural en nuestra comunidad desaparecería y con él todo un bagaje de conocimientos que aun no hemos explorado.

Labels: Pesca

Pulpos y anuncios -Pepsi-

Published Saturday, May 20, 2006 by Spyder.Hacía meses que lo quería colgar, pero no había encontrado la ocasión (este medio hasta ahora se había despreocupado de los temas publicitarios). Pero hemos decidido que si hoy pasan por aquí, se sientan como en casa, en un tarde de Sábado delante de algún televisor. Usted puede aprovechar el momento para vaciar su vejiga, prepararse unos cuantos pochoclos, o apagar televisor u ordenador y disfrutar de algo de sexo con su pareja (sin duda lo más productivo incluso en el sentido bíblico). Volvemos en unos minutos.

Busqué este video por internet, y lo crean o no, me encontré con un montón de almas en pena que habían hecho lo mismo. Foros donde se dejaban de mensajes. “Alguien tiene el video...?” “Quiero disfrazarme de pulpo, alguien podría conseguir...? Cuando después de dar vueltas y vueltas, estaba a punto de darme por vencido, se me ocurrió que podía buscarlo en ya no recuerdo que lugar (tic quijotesco). Lo encontré. ¡Yo era ese alguien que buscaban los desorientados penitentes! Y supongo que difundiéndolo desde aquí voy hacer feliz a algunos carnavaleros o fanáticos de los anuncios.

Por si esos me googlean las palabras clave podrían ser: PULPO PEPSI FIESTA DISFRAZ.

Ah! Se me olvidaba, la canción es de Bonnie Tyler y canta Holding out for a hero.

Labels: Publicidad

Arte y pulpos -Aimee Ray-

Published Friday, May 19, 2006 by Spyder.Cabellos y tentáculos… juraría que esto me suena. Ilustración de la artista Aimee Ray.

La página personal de la artista se llama Dreamfollow, que debe ser algo así como persigue el sueño. Pues en eso estamos...

Vía Dreamfollow

Aimee Ray

Aimee Ray currently resides in the Ozark mountains of NW Arkansas with her husband Josh, their two dogs, Gypsy and Gryphon. She has a BFA inGraphic Design/ Illustration and works by day as a designer/ illustrator for a Christian greeting card company. She also works on various freelance comic book projects doing coloring, lettering and inking. In her spare time she does art for herself, which is what you'll find here. She has been an artist all her life, but in the last few years has found herself with an internal drive to create. Her mind is always full of ideas and often has several muses pulling her in different directions! Picking one to listen to at a time can be a challenge. She is inspired by her many books of fantasy and folklore, dreams, other artists, and most of all, God's creation- animals and nature. Her favorite tools are watercolors, colored pencils, her Mac- Photoshop, Illustrator, or a needle and thread.

Labels: Artistas

Pulpos -Envases- Pulpo envasado al vacío-

Published Thursday, May 18, 2006 by Spyder. El pulpo viene troceado, cocido y envasado al vacío, lo que hace que para que esté en su punto únicamente tenemos que descongelarlo y calentarlo unos segundos al horno. Al estar ya cocido nos ahorramos tener que buscar el punto de cocción (se evita que nos quede blando o duro).

El pulpo viene troceado, cocido y envasado al vacío, lo que hace que para que esté en su punto únicamente tenemos que descongelarlo y calentarlo unos segundos al horno. Al estar ya cocido nos ahorramos tener que buscar el punto de cocción (se evita que nos quede blando o duro).Haga el pedido por internet y en 48 h. Se comprometen a llevarlo hasta su casa. Tenga en cuenta que el precio del transporte se mueve entre 10 y 20 euros más.

Labels: Envases, Fotografías

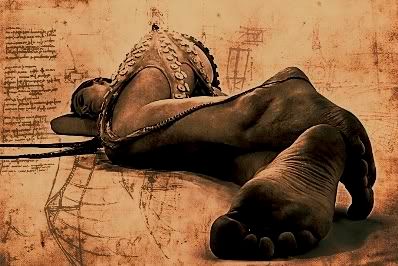

Arte y pulpos -Lisa Alisa- Acariciando sus cabellos

Published Wednesday, May 17, 2006 by Spyder.

Labels: Artistas

Poema de Marianne Moore -An Octopus-

Published Monday, May 15, 2006 by Spyder.Marianne Moore

of ice. Deceptively reserved and flat,

it lies “in grandeur and in mass”

beneath a sea of shifting snow-dunes;

dots of cyclamen-red and maroon on its clearly defined

pseudo-podia

made of glass that will bend—a much needed invention—

comprising twenty-eight ice-fields from fifty to five hundred

feet thick,

of unimagined delicacy.

“Picking periwinkles from the cracks”

or killing prey with the concentric crushing rigor of the python,

it hovers forward “spider fashion

on its arms” misleading like lace;

its “ghostly pallor changing

to the green metallic tinge of an anemone-starred pool.”

The fir-trees, in “the magnitude of their root systems,”

rise aloof from these maneuvers “creepy to behold,”

austere specimens of our American royal families,

“each like the shadow of the one beside it.

The rock seems frail compared with the dark energy of life,”

its vermilion and onyx and manganese-blue interior expensiveness

left at the mercy of the weather;

“stained transversely by iron where the water drips down,”

recognized by its plants and its animals.

Completing a circle,

you have been deceived into thinking that you have progressed,

under the polite needles of the larches

“hung to filter, not to intercept the sunlight”—

met by tightly wattled spruce-twigs

“conformed to an edge like clipped cypress

as if no branch could penetrate the cold beyond its company”;

and dumps of gold and silver ore enclosing The Goat’s Mirror—

that lady-fingerlike depression in the shape of the left human

foot,

which prejudices you in favor of itself

before you have had time to see the others;

its indigo, pea-green, blue-green, and turquoise,

from a hundred to two hundred feet deep,

“merging in irregular patches in the middle of the lake

where, like gusts of a storm

obliterating the shadows of the fir-trees, the wind makes lanes

of ripples.”

What spot could have merits of equal importance

for bears, elks, deer, wolves, goats, and ducks?

Pre-empted by their ancestors,

this is the property of the exacting porcupine,

and of the rat “slipping along to its burrow in the swamp

or pausing on high ground to smell the heather”;

of “thoughtful beavers

making drains which seem the work of careful men with shovels,”

and of the bears inspecting unexpectedly

ant-hills and berry-bushes.

Composed of calcium gems and alabaster pillars,

topaz, tourmaline crystals and amethyst quartz,

their den in somewhere else, concealed in the confusion

of “blue forests thrown together with marble and jasper and agate

as if the whole quarries had been dynamited.”

And farther up, in a stag-at-bay position

as a scintillating fragment of these terrible stalagmites,

stands the goat,

its eye fixed on the waterfall which never seems to fall—

an endless skein swayed by the wind,

immune to force of gravity in the perspective of the peaks.

A special antelope

acclimated to “grottoes from which issue penetrating draughts

which make you wonder why you came,”

it stands it ground

on cliffs the color of the clouds, of petrified white vapor—

black feet, eyes, nose, and horns, engraved on dazzling ice-fields,

the ermine body on the crystal peak;

the sun kindling its shoulders to maximum heat like acetylene,

dyeing them white—

upon this antique pedestal,

“a mountain with those graceful lines which prove it a volcano,”

its top a complete cone like Fujiyama’s

till an explosion blew it off.

Distinguished by a beauty

of which “the visitor dare never fully speak at home

for fear of being stoned as an impostor,”

Big Snow Mountain is the home of a diversity of creatures:

those who “have lived in hotels

but who now live in camps—who prefer to”;

the mountain guide evolving from the trapper,

“in two pairs of trousers, the outer one older,

wearing slowly away from the feet to the knees”;

“the nine-striped chipmunk

running with unmammal-like agility along a log”;

the water ouzel

with “its passion for rapids and high-pressured falls,”

building under the arch of some tiny Niagara;

the white-tailed ptarmigan “in winter solid white,

feeding on heather-bells and alpine buckwheat”;

and the eleven eagles of the west,

“fond of the spring fragrance and the winter colors,”

used to the unegoistic action of the glaciers

and “several hours of frost every midsummer night.”

“They make a nice appearance, don’t they,”

happy see nothing?

Perched on treacherous lava and pumice—

those unadjusted chimney-pots and cleavers

which stipulate “names and addresses of persons to notify

in case of disaster”—

they hear the roar of ice and supervise the water

winding slowly through the cliffs,

the road “climbing like the thread

which forms the groove around a snail-shell,

doubling back and forth until where snow begins, it ends.”

No “deliberate wide-eyed wistfulness” is here

among the boulders sunk in ripples and white water

where “when you hear the best wild music of the forest

it is sure to be a marmot,”

the victim on some slight observatory,

of “a struggle between curiosity and caution,”

inquiring what has scared it:

a stone from the moraine descending in leaps,

another marmot, or the spotted ponies with glass eyes,

brought up on frosty grass and flowers

and rapid draughts of ice-water.

Instructed none knows how, to climb the mountain,

by business men who require for recreation

three hundred and sixty-five holidays in the year,

these conspicuously spotted little horses are peculiar;

hard to discern among the birch-trees, ferns, and lily-pads,

avalanche lilies, Indian paint-brushes,

bear’s ears and kittentails,

and miniature cavalcades of chlorophylless fungi

magnified in profile on the moss-beds like moonstones in the water;

the cavalcade of calico competing

with the original American menagerie of styles

among the white flowers of the rhododendron surmounting

rigid leaves

upon which moisture works its alchemy,

transmuting verdure into onyx.

“Like happy souls in Hell,” enjoying mental difficulties,

the Greeks

amused themselves with delicate behavior

because it was “so noble and fair”;

not practised in adapting their intelligence

to eagle-traps and snow-shoes,

to alpenstocks and other toys contrived by those

“alive to the advantage of invigorating pleasures.”

Bows, arrows, oars, and paddles, for which trees provide the

wood,

in new countries more eloquent than elsewhere—

augmenting the assertion that, essentially humane,

“the forest affords wood for dwellings and by its beauty

stimulates the moral vigor of its citizens.”

The Greeks liked smoothness, distrusting what was back

of what could not be clearly seen,

resolving with benevolent conclusiveness,

“complexities which still will be complexities

as long as the world lasts”;

ascribing what we clumsily call happiness,

to “an accident or a quality,

a spiritual substance or the soul itself,

an act, a disposition, or a habit,

or a habit infused, to which the soul has been persuaded,

or something distinct from a habit, a power”—

such power as Adam had and we are still devoid of.

“Emotionally sensitive, their hearts were hard”;

their wisdom was remote

from that of these odd oracles of cool official sarcasm,

upon this game preserve

where “guns, nets, seines, traps, and explosives,

hired vehicles, gambling and intoxicants are prohibited;

disobedient persons being summarily removed

and not allowed to return without permission in writing.”

It is self-evident

that it is frightful to have everything afraid of one;

that one must do as one is told

and eat rice, prunes, dates, raisins, hardtack, and tomatoes

this fossil flower concise without a shiver,

intact when it is cut,

damned for its sacrosanct remoteness—

like Henry James “damned by the public for decorum”;

not decorum, but restraint;

it is the love of doing hard things

that rebuffed and wore them out—a public out of sympathy

with neatness.

Neatness of finish! Neatness of finish!

Relentless accuracy is the nature of this octopus

with its capacity for fact.

“Creeping slowly as with meditated stealth,

its arms seeming to approach from all directions,”

it receives one under winds that “tear the snow to bits

and hurl it like a sandblast

shearing off twigs and loose bark from the trees.”

Is “tree” the word for these things

“flat on the ground like vines”?

some “bent in a half circle with branches on one side

suggesting dust-brushes, not trees;

some finding strength in union, forming little stunted grooves

their flattened mats of branches shrunk in trying to escape”

from the hard mountain “planned by ice and polished by the wind”—

the white volcano with no weather side;

the lightning flashing at its base,

rain falling in the valleys, and snow falling on the peak—

the glassy octopus symmetrically pointed,

its claw cut by the avalanche

“with a sound like the crack of a rifle,

in a curtain of powdered snow launched like a waterfall.”

Marianne Moore (EEUU, 1887-1972)

Marianne Moore nació en 1887 en Saint Louis (Missouri, EE.UU.) y murió en 1972 en Nueva York. Integrante de la primera generación de poetas modernos de su país, junto con T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound o William Carlos Williams, fue maestra entre sus coetáneos, muchos de los cuales apreciaron y elogiaron su obra, que recibió los premios Pulitzer, Bollingen y Dial. Su trabajo destaca por la búsqueda de lo auténtico en lo concreto. Aunque aparentemente impersonal y objetiva, a través de lo sinuoso, del eufemismo, la negación y lo intermitente, produjo una poesía subversiva en la que las múltiples voces y la interacción entre los reinos de la naturaleza y la cultura consiguen una gran tensión planteando problemas sin resolverlos y forzando al lector a extraer sus propias conclusiones. Se trata de una obra original, independiente y modélica, cuya influencia y vigencia se han mantenido vivas a lo largo del siglo.

Labels: Poemas

Octopus Cam

Published Sunday, May 14, 2006 by Spyder.Aquatic Animals

Labels: Curiosidades

Pulpo Gigante -Adopta un pulpo gigante!-

Published by Spyder. Si vas a Washington D.C podrás visitar el Zoo Nacional que depende del Instituto Smithsonian. El zoo tiene un programa de adopciones, por lo que no le será dificil adoptar uno de sus pulpos gigantes. Ahora, eso sí, usted no se lo podrá llevar a casa.

Si vas a Washington D.C podrás visitar el Zoo Nacional que depende del Instituto Smithsonian. El zoo tiene un programa de adopciones, por lo que no le será dificil adoptar uno de sus pulpos gigantes. Ahora, eso sí, usted no se lo podrá llevar a casa.Giant Octopus—

Adopt a Giant Octopus!

With its writhing tentacles and eerie ability to figure things out, the octopus is one of the strangest animals in the sea, or on Earth, for that matter. Its alien appearance and sliminess unnerve some people, offering plenty of material for nightmares and legends. Octopus stories abound around the globe, including seafaring yarns about huge, blood-thirsty “devilfish” tearing ships to bits. While these stories are usually debunked, the uncanny abilities and physique of the remarkable giant octopus make these tales hard to let go.

Large, but Short-Lived MolluskThe largest of at least 90 subspecies of octopus, the giant octopus can grow to 300 pounds and have a 30-foot arm span. However, mature males average only about 50 pounds and females, about 33 pounds. Their arm spans typically are about eight feet. Despite its fearsome appearance, the giant octopus—while quite resourceful—is very shy and poses little danger to divers, fishermen, or swimmers. These mollusks are distant relatives of garden snails and slugs, and closer relatives of squids and cuttlefish. The giant octopus can be found in the coastal waters of northern California through the Gulf of Alaska, and around the Pacific Rim to Japan and Korea. They live in waters just beyond the low-tide mark to depths of up to 1,500 feet along the continental shelf. They usually live about three to five years.

A giant octopus spends most of its day lurking in a rocky crevice, emerging at night to forage for prey. When it ventures out, it typically crawls along the sea floor, often with surprising speed. Above the floor, it propels itself by a water jet thrust out through its gill chamber.

A giant octopus eats almost anything it can catch, with crabs at the top of its list of favorites. It also catches fish and other octopuses. It hunts mainly by sight. The octopus surges forward and envelops prey with its strong tentacles. Its suckers have touch sensors and chemical receptors that it uses to check out its catch, allowing it to reject anything that feels or tastes wrong. Sometimes the octopus paralyses its victim with venom from its salivary glands, but usually it just rips prey apart with its powerful suckers. The octopus kills crabs with a shell-crushing bite from the parrot-like beak concealed at the center of its tentacles. It then scoops out the flesh and discards any shell outside its lair.

Male giant octopuses mature sexually before females. During mating, the male uses a specialized tentacle to insert a sperm packet into the female. The male dies soon after mating. The female produces up to 100,000 eggs, which she attaches to the ceiling of her den. She guards her eggs for six months, never eating or even leaving her den. She oxygenates her eggs by shooting water over them from her gills. Exhausted by breeding and starved by the vigil over her eggs, the female dies almost as soon as the eggs hatch. Each egg hatches into a tiny octopus about one-quarter of an inch long. Baby octopuses swim to the surface to live as plankton—tiny plants and animals that drift in the ocean—until settling on the seabed when about one-half ounce in weight where it grows at an amazing rate—reaching two to three pounds in one year and then continuing to gain about two percent of body weight per day! Few hatchlings, however, ever reach maturity before becoming food for fish, moray eels, sea lions, or other octopuses.

Intelligent Invertebrate?The giant octopus has the largest central nervous system—mostly brain—of all invertebrates, rivaling that of many vertebrates, including birds and fish. It can do some really amazing things. But is it intelligent? Herein lies much debate-fodder for scientists. The fact that octopuses survive despite being soft, tasty creatures suggests to some that they are resourceful and intelligent. They also appear quite capable of solving simple puzzles, learning, and remembering. Scientists have trained captive specimens to negotiate their way through simple mazes and distinguish squares from crosses. They have been taught to unscrew lids from food jars and have been observed learning by watching the behavior of other octopuses.

But other scientists aren’t so sure that big brains mean greater intelligence. They suggest that a big brain may be necessary to operate such a complex animal with sophisticated eyes, eight versatile tentacles, ability to change color, sensitive suckers.

Dazzling Array of Defensive and Offensive Weapons

Suckers. The octopus uses its suckers to rip prey apart and anchor itself to a rocky surface. Sensors around each sucker allow the animal to reject anything that tastes or feels wrong.

Tentacles. The octopus has eight strong arms capable of pushing, pulling, and grasping prey tightly.

Beak. The giant octopus uses its powerful beak to crush crab shells.

Venom. Venom in its salivary glands contains a chemical that helps the octopus disable prey and break down its muscle tissue.

Ink. The octopus can disorient a pursuer by squirting a burst of purplish-black ink.

Appendage Regeneration. Should the animal lose a tentacle to a predator, it can grow a new limb.

Camouflage. The octopus can change the color and texture of its skin cells in less than one second to blend in with its surroundings. These cells in its skin called chromatophores are under muscular control, allowing different pigments to come into view as the cell walls are stretched or squeezed. One expert suggests that “Chameleons are just dead-boring compared to octopuses.”

Giant Octo-Facts

A giant octopus can live out of water for some time as long as it stays cool and damp. It may leave the water to search for food on land. To snatch quick snacks, octopuses have been known to climb aboard fishing boats and open fish holds full of crabs or to break out of aquariums to prow around rooms for tasty inhabitants in other tanks. They generally have up to one-half hour out of water before they die from lack of oxygen.

Octopus blood is a poor carrier of oxygen. To compensate, these animals have three hearts and permanently high blood pressure. As a result of these physiological inefficiencies, the octopus has poor stamina and an inability to struggle offensively or defensively for very long.

By day giant octopuses retreat to dens under rocks or in holes. At the entrance, one typically observes an “octopus’s garden” composed of a collection of bones, spines, and shells from past meals.

An octopus can squeeze through an opening no bigger than one of its eyes.

An octopus’s brain continues to grow throughout the life of the animal and consists of over 170 million nerve cells, three-quarters of which are involved in vision.

Conservation StatusGiant octopuses are important members of the oceanic web of life. As hatchlings they enter the low end of the food chain—the diverse plankton soup—that feeds myriads of animals. As they grow to maturity, they climb to almost the top of the ocean’s food chain to become a formidable predator.

The giant octopus is currently not considered endangered, and some intrepid enthusiasts keep them as pets, although this requires a major commitment. The giant octopus is vulnerable to pollution, but unlike its edible relative, the common octopus, it is not in direct danger from humans even though there is a small commercial fishery for it from Alaska to Northern California, mainly as a bait for halibut fisheries. In Oregon, many octopus are taken as incidental catch in the Dungeness crab pot fishery and the groundfish trawl fishery. Octopus overfishing, however, appears to have occurred in Japan and in sport dive fisheries in the straits between Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia.

Enriching an Octopus’s Life—the Zoo ExperienceThe National Zoo currently has a female giant octopus in residence at its Invertebrate Exhibit. It is a very popular animal at the Zoo mainly because, unlike many Zoo animals, the giant octopus is familiar to most visitors through stories. Also, adding to its appeal, the animal is large and gregarious, never missing an opportunity to react and interact. Few can resist the opportunity to look the octopus in the eye and have it stare back. One keeper calls the giant octopus “the Invertebrate Exhibit’s giant panda.” This popular mollusk is fed a diet of shrimp, fish, and crab.

To provide this fascinating animal opportunities for exploration and interaction similar to those observed in the wild, the Zoo has implemented an Octopus Enrichment Program. Under the watch of a trained observer, a new object—such as a jar, tube, or rubber dog toy—is introduced periodically to the octopus. With each introduction the animal's behavior is recorded to identify the level of interaction with the object. In addition, the tank contains shelves, archways, and doors. New objects and complexities are planned for the future to give this mollusk with a sophisticated brain a new and broader array of challenges.

Adopt a Giant OctopusWhy not consider adopting this wild and wonderful giant from the deep for yourself or for a special someone? An Adopt a Giant Octopus package would make an especially wonderful educational gift for a child. Your adopt contribution will support exhibit improvement, medical care, and food not only for the giant octopus but also for the more than 2,400 other animals that reside at the National Zoo and its Conservation and Research Center at Front Royal, Virginia.

Labels: Monstruos marinos

Pulpo gigante: el pez diablo

Published Friday, May 12, 2006 by Spyder. Los misterios del mundo animal , Pulpo Gigante: el pez diablo

Los misterios del mundo animal , Pulpo Gigante: el pez diablo Ricardo Santiago Katz (*)

rskatz4@hotmail.com

Labels: Monstruos marinos

Pulpo gigante de Hawai

Published Thursday, May 11, 2006 by Spyder.Se han publicado dos testimonios de avistamientos de pulpos gigantes en el archipiélago hawaiano en los años 1950. Según las descripciones, los brazos, de más de veinte metros de longitud, estaban cubiertos de grandes ventosas, lo que puede indicar que se trata de pulpos incirrados, a diferencia del pulpo gigante de las Bahamas. Además, los lugares donde se observaron los pulpos son semejantes: En los dos casos se trataba de zonas poco profundas cercanas a lugares de anidamiento de tortugas marinas. Pero, desde entonces, no se han vuelto a tener noticias.

Labels: Monstruos marinos

Pulpo gigante de las Bermudas

Published by Spyder.Labels: Monstruos marinos

Pulpo gigante de las Bahamas

Published Wednesday, May 10, 2006 by Spyder.Labels: Monstruos marinos

Pulpo gigante -In the Octopus's Garden-

Published Tuesday, May 09, 2006 by Spyder.by Julie Zeidner Russo

The sighting of fantastic sea creatures like the giant octopus have been portrayed throughout history. Probably the first recorded mention of something that resembles an octopus was the monster Scylla in Homer's Odyssey. At the dawn of a new millennium, the giant octopus is not so much a folkloric figure as a culinary delicacy for the Japanese, a staple in some Native American diets, and a subject of rare scientific scrutiny.

There is still much to learn about the giant octopus beyond its role in fiction or as a food source. Taste for the giant octopus could make it subject to an eastern Pacific commercial fishery before long. This increasing demand comes well in advance of an understanding of how and where the giant octopus lives.

A wealth of information on what is known about the giant octopus can be found at marine ecologist David Scheel's web site at http://www.pwssc.gen.ak.us/~dls. Reading through the site, one learns a great deal about the largest species of octopus in the world known as Enteroctopus dofleini. Although the giant octopus rarely weighs more than 100 pounds (45 kg), a few large individuals have been recorded up to 400 pounds (182 kg). While there are more than 100 species of octopuses in the world, our knowledge of octopuses comes almost entirely from a few species, Scheel said.

An intensive effort to learn more about the giant octopus commenced after the Exxon Valdez oil spill impacted the area. The Prince William Sound Science Center (PWSSC), a nonprofit research institute where Scheel is an associate scientist, was established in response to the environmental disaster.

The institute's focus would be on ecological research associated with the Prince William Sound and Copper River Watersheds in Alaska. Their work would be important since the Sound is one of the last major glacial carved embayments on the northwestern edge of a temperate coastal zone with rainforest biodiversity. "It's a really amazing area with a very complex history of coastal peoples," Scheel said.

A coastal tradition was upset following the 1989 oil spill. The native villagers in Tatitlek and Chenega Bay eat amikuq (the Alutiiq word for octopus) as part of their subsistence lifestyle. They reported that octopuses became scarce in the years following the 1989 oil spill, Scheel said. A two-year study was launched by Scheel and co-investigators to survey octopuses from the shoreline to 30 feet. The study was paid for by the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. The researchers adopted the technique used by native villagers when harvesting octopus that den under rocks and are exposed at low tide as a means of counting and characterizing octopuses. They found densities an order of magnitude--10 to one--less than a survey done in British Columbia by scientist Brian Hartwick in the '70s and early '80s, Scheel said. Researchers did not have enough information about the giant octopus to attribute this difference to the more northern study area in Prince William Sound, or to a decline in abundance from man-made causes or from natural fluctuations in abundance. "It's not clear there was any decline in octopuses," said Scheel, noting more research would have to be done to determine if there was a problem.

In 1996, researchers used SCUBA dives to further investigate where and how the octopus lives and moves, and what it eats. They tagged individuals with sonic tracking devices, and monitored their movements. "SCUBA surveys proved that octopuses were more abundant on shallow dives (to five m.) than on deep dives," Scheel said. The researchers also found an abundance of juvenile octopuses, and very few adults. Where had they gone? To determine whether depth is significant in the ecology of the giant octopus researchers would need to dive deeper.

The chance to go deeper in search of the adult giant octopus occurred in May of 1998. This would be the first time researchers ever provided descriptions of octopus habitat below SCUBA depths. Scheel and ecologist Tania Vincent, also of the PWSSC, made 27 dives in the Delta submersible with support from the NOAA's Undersea Research Program (NURP).

"Using the submersible, we were able to go down and find octopuses too small to be caught by pots or long-line," Scheel said, "as well as survey the habitats, the predators, and the prey base." Scheel and Vincent would conduct 20 1000 m long transect surveys, three dives tracking a sonic-tagged octopus, and four dives to resurvey areas explored during the earlier SCUBA research and other sites of interest.

Giant octopuses have a unique life history that is only partly understood. They live across the broad continental shelf of the north Pacific ocean in a range extending from southern California to the Pacific Northwest, across the Aleutians, and south to Japan, Scheel said. They exist in shallow waters to 200 m, and may occur deeper. What happens to them during their short life span of three to five years is not fully known.

Females lay as many as 100,000 eggs inside of a rocky den and tend to them. "They senesce and die at about the time the eggs hatch," Scheel said. The males, who move around during the mating period, also die a few months later. On hatching, baby octopuses enter the plankton till they get big enough to settle down to the bottom again. After settlement, dens are an important resource for the octopus. Dens are not only used by the females for tending to their eggs, but serve as a place to hide from other predators.

"Marine mammals that feed on octopuses include seals, sea lions, sea otters, and killer whales, at least," Scheel said. Their dens-nicknamed the Octopus's Garden-also reveal a lot about them. Researchers study the middens or refuse heaps outside the octopus den to learn more about their diets, which include crustaceans, small crabs, scallops, bivalves, snails, fish, and even other octopuses.

Prior to the NURP study, the researchers understanding of the ecology of the giant octopus in rocky habitats of the eastern Pacific came from surveys to 30 m. Determining the abundance of octopuses below 30 m would be a key part of this study. Researchers theorized that since octopuses were nearly absent from depths between 10 and 30 m. in Prince William Sound, but abundant in shallower waters, that the very shallow areas might be important rearing habitat, Scheel said. They would need data from deeper areas to compare. There also appeared to be an abundance of octopuses living in heavy kelp beds in shallow areas, which may provide shelter from predators. "We thought octopuses may be restricted by high predation risk from using habits at intermediate depths to 40 meters," Scheel said. "If this were true, we anticipated that larger octopuses would be more common in deeper water; and that there might be more octopuses of all sizes."

What researchers discovered puzzled them. During the Delta dives from10 to 200 meters, Scheel and Vincent only found a total of 19 octopuses and only one was of adult size. "Contrary to our expectations, we found that larger octopuses were rare at any depth," Scheel said, "and although we found octopuses at all depths to 200 m, we found no indication of greater numbers of octopuses as we went deeper." However, they did note changes in the denning habits and diets of the octopuses at greater depths.

In order to manage the octopus fishery, resource managers will have to learn more about the natural fluctuations in octopus populations. Japan already has a large commercial fishery for octopus. While no commercial east Pacific fishery exists yet, interest is growing in developing one by parties in Japan, Africa, Greece, Alaska, and British Columbia.

"Fisheries scientists believe it would only take small changes in market demand for octopuses to trigger an increased commercial fishing effort," Scheel said. "This creates a possibility of over-exploitation of the stock, a matter of particular concern in the Gulf of Alaska coastal areas in light of damage to octopus habitat during the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 and the subsistence harvests of octopuses by native peoples."

Centuries later, the giant octopus still has the capacity to intrigue us, but whether it can endure time before it is fully understood is questionable. There must have been other giant sea creatures that existed long ago that would have certainly marveled us today had they not perished. This makes understanding great animals that we know exist like the giant octopus seem all the more precious, if not critical. "The solitary nature and excellent camouflage abilities of the octopuses make them hard to count," Scheel said. While this helps protect them against natural predators, it makes it difficult for fisheries managers to conduct stock assessments to determine how they are faring and how they might be properly managed.

"Managers are considering whether an assessment based on mapping suitable habitat would provide a means to assess the population," Scheel said. "However, even habitat mapping is limited by our understanding of octopus habit ecology. This research should improve what is known about the giant octopus, so that enough information is available to prevent octopuses from being overexploited as a fisheries resource.

Labels: Monstruos marinos

Octopus giganteus

Published by Spyder.Mike Tatzel

The object that started the commotion was a rotting carcass of great size. It was first seen by Herbert Coles and Dunham Coretter on a bicycle trip on the evening of November 30, 1896. The following event could have been of extreme zoological importance. What was instead ignored and ridiculed could have been one of the greatest zoological discoveries in history.

When the young men first saw the carcass, it had sunk into the sand because of its immense weight. The next day, Dr. DeWitt Webb, founder of the St. Augustine Historical Society and Institute of Science, arrived on the scene. The skin was of an extremely light pink color with a silvery tint to it. They concluded it weighed roughly five tons and the visible portions were twenty-three feet in length, four feet high, and eighteen feet across the widest part of the back. Webb, decided that it was not a whale but only some kind of octopus.

It was then that Webb sent several letters describing the carcass to scientists. Professor Verrill of Yale read one of them. Verrill, a zoologist, was recognized for his work on cephalopods, especially giant squid. In a note in the American Journal of Science, published January 1897, he concluded the animal was a giant squid, not an octopus, but much larger that the Newfoundland specimens he had examined. Webb then forwarded more photographs and information to Verrill, who changed his theory to an octopus. He wrote more notes to the American Journal of Science describing the new giant octopus. He concluded the specimen’s tentacles to be approximately seventy-five to one hundred feet long by eighteen inches at the base. He then designated the new creature Octopus giganteous verrill, after himself.

It would be into the second week of January that the work on the specimen would continue. The carcass had been washed out to see again resulting in further losses of body parts and mutilation of the carcass. He reported to both Verrill and Professor William Healy Dall, curator of mollusks at the National Museum in Washington DC, now called the Smithsonian, by letter. In spite of this, neither Verrill nor Dall made any effort to investigate the carcass for themselves nor were they willing to provide the time and money to properly preserve the animal.

Using teams of horses and the efforts of local citizens and companies, Webb was able to move the carcass further up the beach. This protected the remains from being permanently washed out to sea where they would have been lost forever. He then prepared specimens for Verrill and Dall. They were both taken from the mantle of the creature and preserved in formaldehyde. This would turn out to be the only hard evidence to future scientists to study. Webb was, however, interested in preserving the whole carcass and preservatives were forwarded.

Verrill received Webb’s preserved specimen on February 23 and wrote letters of reaction that were published in Science on March 5, 1897, and in the Herald on the seventh. He described the samples visually and concluded they could not be octopus tissue because they resembled the blubber found in some crustaceans, despite the fact that little oil was found in them. Professor Frederic Augustus Lucas, of the National Museum, also examied the speciems and stated "the substance looks like blubber, and smells like blubber, and it is blubber, nothing more nor less."

Verrill finally concluded, after further examination of the tissues, that the bag-like section of the carcass was most likely the upper head and nose of a sperm whale. In the issues of the American Journal of Science and the American Naturalist for April, he does not try to make the objections and problems with his sperm whale theory less obvious. He pointed out that other zoologists that examined the carcass still believe it is an unknown cephalopod related to the octopus.

No work was done on the specimen until 1957 when Dr. F. G. Wood became interested and involved Dr. Joseph F. Gennaro Jr. Gennaro made a trip to the Smithsonian to collect the specimen and wrote:

There by the sink was a glass container about the size of a milk can. Inside it was a murky mixture of cheesecloth, formalin (and I think some alcohol), and half a dozen large white masses of tough fibrous material, each about as large as a good sized roast. We lifted them up with the cheesecloth, then took them out with forceps.

He noted that the material corresponded to Webb’s description. He was allowed to remove what he wanted with a dissecting knife with replaceable blades. The two pieces he removed were wrapped in cheesecloth, placed in a jar, and transported by himself to his laboratory.

Initial examination proved disappointing. There were no features such as suckers, identifiable skin structures, or muscular masses. He then viewed them through a microscope along with control specimen samples of known octopus and squid. He was disappointed to find no cellular fine structure. He expected highly differentiated cells of a mammal if it was from a whale or structures typical of a squid or octopus. Then he viewed his control samples. They also revealed little if any cellular structure. Differences of connective tissues were more striking. Octopus tissue was different from squid tissue and neither could be mistaken for mammalian tissue.

Using polarized light, Gennaro decide to compare connective tissues. His findings were as follows:

Now differences between the contemporary squid and octopus samples became very clear. In the octopus, broad bands of fibers passed along the plane of tissue and were separated by equally broad bands arranged in a perpendicular direction. In the squid there were narrower, but also relatively broad, bundles arranged in planes of the section, separated by thin partitions of perpendicular fibers….It seemed I had found the means to identify the mystery sample after all. I could distinguish between octopus and squid, and between them and mammals, which display a lacy network of connective tissue fibers….After seventy-five years, the moment of truth was at hand. Viewing section after section of the St. Augustine sample, we decided at once and beyond any doubt, that the sample was not whale blubber. Further, the connective tissue pattern was that of broad bands in the plane of the section with equally broad bands arranged perpendicularly, a structure similar to, if not identical with, that in my octopus sample….The evidence appears unmistakable that the St. Augustine sea monster was in fact an octopus, but the implications are fantastic.

We can agree with the assessment but should not be surprised that giant octopi have not been verified before. Perhaps the giant sucker marks on whales, particularly sperm whales, are not caused by giant squid, but rather by giant octopus, as they are more sluggish and are bottom dwellers. Where would these creatures be found? Wood’s investigations revolved around the Bahamas, where reported creatures known as the Lusca very clearly resemble that of giant octopi.

Interestingly enough, Wood had worked in the area in 1956, surveying possible sites for Marine Studios. At one point he recounted vague references to "giant scuttles." "Scuttle" is the Bahamian word for octopus. A reliable guide with whom he worked, named Duke, maintained that the scuttle’s arms were about seventy-five feet long. He also said they are not dangerous to fishermen unless they can grip the ocean floor and the boat at the same time. Additional information was received by George. J. Benjamin, who was intrigued by the great blue holes in the ocean floor around the Andros Islands. He nor his colleagues ever observed any octopi or squid on their investigations of the holes.

However, it seems that evidence presented, consisting not only of reports but also tissue samples, establishes that very large octopi exists somewhere in the Atlantic off the Florida coast. Whether these creatures explain the Lusca cannot be determined until deep diving exploration is carried out in the area.

It seems that other carcasses besides the now famous St. Augustine monster have been observed. In fact, many references can be found to unidentified sea creatures, dubbed globsters, that have washed ashore, some of which resemble the giant octopus. One such body found in Tasmania in August 1960 may have been another octopus. Unfortunately, the investigation that followed was worse than that for the St. Augustine carcass. The discovery was made by a rancher and two cowhands but did not reach the capital until months later. An aerial search located it and a four-man expedition was dispatched in March 1962 led by Bruce Mollison from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization. They described the hairy carcass as having no eyes or bones and having creamy, rubbery skin. It was marked with what may have been gill slits. It was given headline treatment and even discussed in Parliament. A zoological team was sent by the government to investigate and returned the next day. Because of the time it had spent decomposing on the beach they said:

"…it is not possible to specifically identify it from our investigations so far. But our investigations lead us to believe that the so-called monster is a decomposing portion of a large marine animal. It is not inconsistent with blubber."

Mollison did not swallow their solution as easily as the press. He claimed they had to say it was ordinary to cover up the fact they were not fast enough to be able to investigate properly. What he saw was not part of a whale, he stated. Theories about the classification of the lump of flesh ranged from a thawed mammoth from Antarctic ice to a space-being. A.M. Clark from the University of Tasmania thought it might have been a giant ray.

Surprisingly, the same rancher who had first seen the Tasmanian globster stumbled across another carcass in 1970. He was in no way excited about it, remembering the ridicule he had gone through the first time. Hardly anyone rushed to investigate the carcass that could have put an end to the mystery of the 1960 carcass.

Other globsters include one that, in March 1965, washed up on the eastern shore of North Island in New Zealand. It was hairy, thirty feet long and eight feet tall. No other significant information was published. On Mangrove Bay beach in Bermuda in May 1988, tissue samples were taken of which laboratory results have yet to be released. Its discoverer, Teddy Tucker, described it as "three feet thick…very white and fibrous…with five arms or legs." Its flesh was extremely hard to cut even in the absence of bone. More recent globsters include that which was found on Four Mile Beach, Tasmania, in 1997. DNA testing was to be done but the results of those tests have never been published.

Marine biologists have turned their attention to those animals living in the unexplored ocean depths, where giant squid are believed to exist. Perhaps there is a bright future and possible discovery of the great octopus.

Labels: Monstruos marinos

Los pulpos más grandes del mundo (II)

Published Monday, May 08, 2006 by Spyder. Otro artículo muy interesante escrito por Antonio Pérez Cribeiro desde su Aquarium Finisterrae. El artículo ha sido extraido del blog de Mar de historias en el que reflexiona sobre el mito del Kraken y las posibilidades de que este fuera un pulpo.

Otro artículo muy interesante escrito por Antonio Pérez Cribeiro desde su Aquarium Finisterrae. El artículo ha sido extraido del blog de Mar de historias en el que reflexiona sobre el mito del Kraken y las posibilidades de que este fuera un pulpo. "Dos cosas me admiran: la inteligencia de las bestias y la bestialidad de los hombres"

A lo largo de la historia, hasta los tiempos recientes, el mar se ha presentado como algo misterioso que superaba el entendimiento humano. Ante lo desconocido, las respuestas tenían que venir, necesariamente, de la imaginación. Los mitos servían no sólo para “explicar" lo ininteligible, sino que podían hacer menos temible la cara oculta de los océanos.

Pero algunas leyendas tenían el efecto contrario. Pocas historias del mar fueron tan terroríficas para los marinos de antaño como la del “Kraken". Narra la existencia de un enorme animal, de dimensiones superiores al mástil principal de un gran velero, que en ocasiones surgía de las profundidades, atrapaba algún desafortunado barco con sus brazos y lo hundía. Inevitablemente, toda la tripulación moría ahogada… o devorada por el monstruo.

¿Qué animal era el Kraken? La versión más popular defiende que se trata de alguna especie de calamar gigante, probablemente del género Architeuthis. Sin embargo, la mayor parte de las múltiples interpretaciones que hay sobre esta leyenda, incluyendo numerosas representaciones gráficas, sugieren la hipótesis de que quizás fuese un pulpo gigante.

En este caso, bien pudiera ser un ejemplar similar al hallado en Florida en 1896, identificado por el profesor Verrill, zoólogo de la Universidad de Yale y autoridad mundial en cefalópodos, que le atribuyó un peso total en vida de unas veinte toneladas, con una envergadura próxima a los sesenta metros. Le llamó Octopus giganteus y así fue publicado en el “American Journal of Science" en 1897. Sin embargo, poco después se tuvo que retractar ante la aparición de evidencias de que el “monstruo" probablemente no era tal, sino un simple cadáver de cachalote.

En cualquier caso, teniendo en cuenta la gran diversidad de culturas que mencionan este mito, probablemente el Kraken sea una especie distinta según la parte del mundo que se considere. Aquí, en el Atlántico ibérico, también hay “monstruos": en la costa asturiana varan con relativa frecuencia restos de cadáveres de calamares gigantes, y en Galicia está citada la presencia de especies como el famoso Architeuthis, e incluso pulpos gigantes.

Hechas las oportunas averiguaciones, se confirmó que se trataba de una hembra de la especie conocida como “pulpo de siete brazos", al que los científicos llaman Haliprhon atlanticus y que está reconocido como el octópodo más grande del mundo . Es más pequeño que los grandes calamares de las profundidades oceánicas, pero dentro del grupo de los pulpos es la especie más grande, pudiendo alcanzar los cuatro metros de envergadura total.

Lo de los siete brazos se debe a que los machos desarrollan el tercer brazo de la derecha modificado en una bolsa debajo del ojo, llamado “hectocótilo", que contiene la carga de gametos sexuales masculinos. Durante la cópula, la hembra se queda el hectocótilo. Al no ser visible da la sensación de que los machos de Haliprhon sólo poseen siete brazos en lugar de los ocho habituales en los octópodos, y que dan lugar a su nombre común. La familia Haliphronidae está considerada actualmente como monotípica, al ser Haliphron atlanticus la única especie reconocida . Su cuerpo es relativamente corto, comprende un tercio de la longitud total, y está fuertemente pigmentado en tono rojo oscuro. Posee ojos grandes, con un diámetro de aproximadamente el cuarenta por ciento de la longitud del manto. Los brazos son largos, también intensamente pigmentados, y tienen dos filas de ventosas cerca de la punta, mientras que en la zona próxima al cuerpo posee una sola fila.

El buen desarrollo del pico y del aparato masticador, junto con la existencia de un aparato de cierre del gran sifón con el manto, induce a pensar que Haliphron es un depredador bastante activo. Haliphron atlanticus vive en alta mar, con un amplio rango de distribución en profundidad. Aunque existen registros de adultos que fueron capturados cerca de la superficie, la mayoría de los especímenes han sido obtenidos entre los 300 y los 1.500 metros. Están presentes en aguas tropicales y frías de todo el mundo. Se cree que los adultos son bentónicos, que viven en el fondo, mientras que los recién nacidos son pelágicos, nadando libres en el agua, de forma que según crecen habitan zonas más profundas.

Las profundidades de los océanos constituyen los hábitats más extensos de la Tierra y a la vez los más desconocidos. Para acceder a ellos se necesita una tecnología equiparable a la utilizada en la investigación espacial, por lo que no es de extrañar que a modo de símil con el “espacio exterior", a estas zonas se les denomine “espacio interior". Valga como referencia el hecho de que el hombre ha hecho más expediciones al espacio que al fondo del mar. La exploración de estas vastas regiones marinas ha avanzado considerablemente en los últimos años, y a buen seguro que nos deparará grandes sorpresas en el futuro.”

Labels: Monstruos marinos