Cocina oriental -Compramos algo en Tako Pachi??-

Published Saturday, September 30, 2006 by Spyder.

3 bolas por 2$ en Tako Pachi, una de las cadenas que vende en Singapur el Takoyaki japonés (bolas de pulpo rebozado con mayonesa encima).

No se ustedes, pero yo miro estas imágenes y se me hace la boca agua...

Labels: Gastronomía

Cocina oriental -El Takoyaki japonés-

Published Friday, September 29, 2006 by Spyder.Via Wikipedia

Las fotógrafias están tomadas del blog de Seru-Kun

El post que coloca es muy interesante. Copio un fragmento.

Takoyaki wa sugoi desuuu!!

...pese a que a Patty no le guste lo más mínimo. La frase se traduce como "¡¡El takoyaki es fantásticooo!!".

Labels: Gastronomía

Cocina -Pulpo a la mugardesa-

Published Monday, September 25, 2006 by Spyder.(Para 4 personas)

Un pulpo fresco de 2 Kg, o en su defecto congelado

2 Kg de patatas

1 cebolla grande

2 pimientos morrones

aceite de oliva

pimenton dulce y picante

Preparación

Si el pulpo es fresco lavarlo bien y después hay que “mazarlo” como dicen en Galicia , es decir hay que darle golpes (como si le dieras una paliza con un palo) para que ablande. Si es pulpo congelado, no es necesario mazarlo ya que el congelado (4 o 5 días) lo ablanda también.

PD. Y el brandy que comentábamos ayer???? Esto lo arreglamos enseguida.

¿Recuerdan el pavo al Whisky? Pues hacer lo mismo con el pulpo al brandy....

PAVO AL WHISKY

Ingredientes:- Un pavo de unos tres kilos- Una botella de whisky- 250 gramos de zanahorias- Medio kilo de patatas- Unas tiras de panceta- Aceite de oliva- Sal y pimienta

Paso 1.- Limpiar el pavo, rellenarlo con la panceta, atarlo, salpimentar y ponerle un buen chorrito de aceite de oliva.

Paso 2.- Pelar y trocear las patatas y las zanahorias, y alfombrar con ellas la bandeja del horno.

Paso 3.- Precalentar el horno a 180 grados durante quince minutos.

Paso 4.- Servirse un vaso de whisky para hacer tiempo.

Paso 5.- Meter el pavo al horno.

Paso 6.- Servirse otro vaso de whisky, beberselo y mirar el horno con ojos ligeramente extraviados.

Paso 7.- Boner el terbostato a 150 gramos... grabdos y esberar trenta binutos.

Paso 8.- Servirse odro paso, odros pasos.

Vaso 9.- Al cabo dum drato, hornir el abro bara condrolar y echar un chodreton de pavo al guisqui y odro de guisqui a uno bisbo.

Baso 10.- Darle la vuelta al babo y quebrarse la bano al cerrar elorno, bierda...!

Passso 11.- Intentarr sentarrse en una silla y sebirrse unossss quessitosss bientras pasan los binutosss.

Parso 12.- Retirar el babo del horrrno y luego regogerrrrlo del suelo con un brapo embujandolo a un blato, bandeja o ssssimiliarrrr.

Faso 13.- Rombersssse la sabbbiola al refalar en la graasssa.

Paaaso 14.- Indendar lebandarse sin soltarr la vodella y dras bariosss indendoss decidir que en el suelo sesta fenommmeno.

Aso 15.- Appburar la potella agompanada de aspapas y zahorias dal rededor, adrastrarse asta la gama, y dormir sseeee.

Paso 16.- A la manana siguiente, tomar abundante cafe para el inexplicable dolor de cabeza, comerse el pavo frio con un poco de mayonesa y el resto del dia dedicarlo a limpiar el estropicio hecho en la cocina.

Buen provecho!!!

Labels: Gastronomía, Recetas

Cocina -Espagueti con salsa negra-

Published by Spyder.350 gramos de espagueti.

1/4 de taza de oliva.

1/2 cebolla picada.

2 dientes de ajo picados.

2 jitomates finamente picados.

1 taza de puré de jitomate.

1 sobre de tinta de pulpo.

1/2 kilo de pulpo.

1 hoja de laurel.

Sal al gusto.

1 ramita de epazote.

Procedimiento:

Freír en el aceite de oliva la cebolla, el ajo, el jitomate y el puré. Incorporar la tinta. Añadir el pulpo y el laurel, sazonar. Cocinar 10 minutos. Colocar el espagueti en el platón encima el pulpo, y la ramita de epazote.

Espagueti: Cocer el espagueti en aagua con sal. Escurrir.

Labels: Gastronomía, Recetas

Pulpos y Festejos -Festa do pulpo en Mugardos-

Published Sunday, September 24, 2006 by Spyder.Es curioso que la Wikipedia francesa da más información sobre Mugardos que la Wikipedia en castellano. Es tradicicional que cada año se celebre la tradicional "Festa de pulpo".

Labels: Festejos, Gastronomía

Guillermo Piro -Los pulpos de Italo Calvino-

Published Saturday, September 23, 2006 by Spyder.Italo Calvino lo sabía: literatos y caballeros, entre otras cosas, tienen en común el obligar al cuerpo a adoptar posiciones innaturales: el literato estando sentado, el caballero andando a caballo, lo que por cierto no es muy higiénico que digamos. De todos modos siempre es mejor estar sentados que de pie: se evitan las várices. En realidad, todos los males del hombre, siempre según Calvino, vienen del hecho de haber decidido éste ser un bípedo, cuando su naturaleza le imponía distribuir el peso del cuerpo en las cuatro extremidades. Así es como nuestros progenitores desarrollaron la habilidad de trabajar con las manos, que liberadas de la función locomotora hicieron posible la historia humana. Pero para Calvino el perfecto equilibrio fue alcanzado durante la larga era de permanencia en los árboles. Las glaciaciones nos bajaron de los árboles, condenándonos a una vida que no nos pertenece y que resultó ser un acontecimiento irresistible. No se puede volver atrás. Hemos construido un mundo para bíperos sentados, dice Calvino, que no tiene nada que ver con nuestro cuerpo, un mundo que heredarán organismos más aptos para sobrevivir. Dado que gran parte de su vida la pasó sentado delante de un escritorio, Calvino opinaba que la forma que le hubiera resultado más cómoda es la de la serpiente. Pero se daba cuenta de que disponiendo sólo de la cola para realizar todas las operaciones manuales, algunas de sus capacidades físico-mentales ligadas a la digitación habrían disminuido notablemente: la dactilografía, la consulta de enciclopedias, contar con los dedos y comerse las uñas.

Labels: Literatura

Arte y pulpos -John Bauguess-

Published Friday, September 22, 2006 by Spyder.

John Bauguess

Via Robert Canaga Gallery

For more than three decades John Bauguess has been photographing people in city and rural landscapes, mostly in Oregon.In his photographs in both color and black and white, Bauguess expresses his love of traditions he has known since his childhood in Oregon, as evidenced in images of Grange hall dances and fiddle jams.

"Maybe what I photograph will help remind us that good traditions are worth hanging onto, that these contribute to a kinder society in which simple pleasures such as homespun music and lively conversation help people survive and stay together as families and communities."

It's not always good times in the small towns in his photographs, however. Bauguess also captures the decay and pathos of communities as a result of decline of sawmills and farming that once provided livelihoods and community stability. His photographs of the grittier side of rural life also contain in their starkness and loneliness a commonality with his documentation life in cities and suburbs.

"I think of myself as a recorder of contemporary Oregon history," he says. "At times I am preserving cultural elements that have given the state its identity. In other photographs I have attempted to reveal to people what they don't know about Oregon, perhaps even try to ignore. Two of my most important bodies of work have focused on homeless and disenfranchised people. The pictures of migrant workers living in abandoned cars were made to create questions. Regardless whether these photographs contributed to social change, they may have substantiated evidence for the need of it.

"Some photographs require my getting to know the people, as in the homeless, migrant worker and fiddler series. In the urban landscape, however--where I don't care to live, but like to often visit because it's interesting--I find a theatrical backdrop for a range of moods—sometimes humorous, sometimes disturbing. In these situations I usually keep a distance from the subjects as I quickly record gestures and expressions as they move through the scene. In these pictures the camera in a fraction of a second may capture something of my state of mind about the people and the environment. In situations where I get to know the people, I attempt to become like wallpaper. When the people are comfortable with me, then I can become comfortable, too, and photograph freely. In the cities, when I blend in with the crowd, I also find freedom to photograph."

Born in Eugene, Oregon in 1943, Bauguess has concentrated his personal photographic efforts during the last year learning to convert his photographic printing from the darkroom to the computer and digital printer. A greater need to care for his mother in recent years has forced him to be more at home than photographing in the field. As a result, he is using spare moments to archive 35 years of photography, scanning negatives and slides onto disk. In this process he has started to make black and white archival inkjet prints of photographs, a large number of which he has never or seldom published or displayed. At Robert Canaga Gallery he is displaying both vintage and more recent photographs. In the near future he plans to print a number of limited edition books that contain more than 300 of his best images.

Exhibitions:

Lane Community College, Eugene, OR, 1996, 1988, 1969Grand Central Terminal, New York City, NY, 1995Maude Kerns Art Center and Photo Zone Galleries, Eugene, OR, 1991Oregon Repertory Theatre, Eugene, OR, 1981Umpqua Valley Arts Center, Roseburg, OR, 1978Visual Arts Resources, University of Oregon Museum of Art, Eugene, OR, 1977Crossroads Art Center, Baker, OR, 1976Pearl Street Photo Gallery, Eugene, OR, 1976Brass Rail Tavern, Eugene, OR, 1972Contemporary Crafts Center, Portland, OR, 1970Klamath Art Association, Klamath Falls, OR, 1969Blue Mountain Community College, Pendleton, OR, 1968

Group Exhibitions:

Corvallis Art Center, Corvallis, OR, 1994, 1989, 1988New Zone Gallery, 1989Newport Art Center, Newport, OR, 1988Oregon-Washington Biennial at Maryhill Museum, Goldendale, WA, 1987Public Image Gallery, New York City, NY, 1984Project Space, Eugene, OR, 1983Woodstock, NY Center for Photography, Woodstock, NY, 1979University of Oregon Museum of Art, Eugene, OR, 1962

Publication Credits:

London Independent Sunday Review Magazine, Harrowsmith Country Life, Los Angeles Weekly, Utne Reader, Discovery, Northwest Magazine of The Oregonian; The Oregonian, The Oregon Journal, North American Review, Nature Magazine, Sunset, Harper's, Travel and Leisure, Viking Books, Riverhead Books, LaEspresso Magazine of Italy, Northwest Review, Oregon Quarterly, Oregon Magazine, Christian Science Monitor, The Oregon Stater, North American Review, Gold's Gym Book of Weight Training and Gold's Gym Book of Strength Training by Ken Sprague.

Videos -Camuflaje- Invisible octopus-

Published Tuesday, September 19, 2006 by Spyder.En el propio video hay toda una polémica entre los más de 3000 mensajes que este video ha recibido discutiendo si es un fake o no.

Yo me inclino a que no, el cambio de color es debido a la cualidad de la piel de los pulpos que puede adoptar diferentes colores y texturas de acuerdo con el entorno. Varias personas dicen que han visto el video en Discovery Chanel, lo cual le da una cierta credibilidad. De todas maneras juzguen ustedes mismo.

La verdad es que por más que lo veo, me parece sorprendente.

Labels: Videos

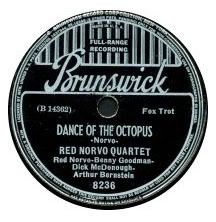

Pulpos y música -Red Norvo- Dance of the Octopus-

Published Monday, September 18, 2006 by Spyder.

Labels: Música

Roger Caillois y el acoplamiento de los pulpos

Published Saturday, September 16, 2006 by Spyder.Aristóteles ofrece del acoplamiento de los pulpos una descripción sucinta: estarían estrechamente enlazados, boca contra boca y brazos contra brazos. Así nadarían conjuntamente, el uno adelante, el otro atrás. Esta disposición es puramente imaginaria. Por mi parte, no he encontrado una descripción objetiva de los amores de los pulpos anterior a la de Henry Lee. El término de descripción, además, conviene mal a las circunlocuciones oscuras y trabadas que el autor, frenado por el pudor Victoriano, utiliza para dar la idea de relaciones sexuales sin embargo excepcionalmente ascéticas. Según él, parece que en el momento de celo se infla el tercer brazo derecho del pulpo macho, de donde sale una especie de gusano alargado terminado por un filamento: es el hectocotilo. El macho lo ofrece a la hembra, quen lo acepta y se lo lleva consigo”

Roger Caillois –Mitología del pulpo-

Labels: Literatura

Pulpos y montajes

Published Friday, September 15, 2006 by Spyder.

Si saben dar buen uso al programa Photoshop, y tienen además imaginación, tiempo y sentido del humor, esta web debería formar parte de sus referencias de la red. La única pega es que todo está allí un poco desordenado y navegar por ahí, es casi peor que hacerlo por Internet (uno más que encontrar lo que busca, se tropieza con lo que encuentra). Pero por suerte todas las galerías son muy divertidas.

Miren por ejemplo la secuencia del barco de la que he extraído el segundo montaje.

Labels: Montajes

Cocina -Pulpo en su tinta-

Published Thursday, September 14, 2006 by Spyder.Ingredientes:

2 kg de pulpos

1 pizca de orégano

1 taza de aceite

1/2 lt. de vino tinto o tres tazas de jugo de naranja

2 kg de jitomate

Sal y chiles en vinagre al gusto

2 cebollas grandes Limones

3 dientes de ajo Aceitunas al gusto

1 manojo de perejil

2 hojas de laurel

Preparación:

Limpie los pulpos (guarde la bolsita de la tinta) y lávelos con jugo de limón. En un recipiente ponga a calentar el aceite y fría el pulpo picado; agregue el jitomate picado, la cebolla, ajo y perejil, también picados. Fría todo y deje hervir a fuego bajo, cuando haya soltado el primer hervor agregue las aceitunas picadas, laurel orégano, jugo de naranja o vino tinto, la tinta de las bolsitas y sal. Deje cocer a fuego bajo hasta que los pulpos estén blanditos; antes de retirarlos del fuego agregue los chiles en vinagre. Sirva acompañado con arroz blanco o hervido.

Labels: Gastronomía, Recetas

El brazo del argonauta

Published Wednesday, September 13, 2006 by Spyder.El macho, que carece de concha, es además unas veinte veces menor que le hembra.

El tamaño no importa

Labels: Características

Pulpos y joyas -De oro y brillantes...-

Published Monday, September 11, 2006 by Spyder.Sobre la conducta sexual del pulpo -Mark Norman- Bizarre Octopus Sex-

Published Sunday, September 10, 2006 by Spyder.Mark Norman: These are the very brittle shells that wash up on southern Australian shores mainly and it's produced by a fairly normal looking octopus that lives in this funny looking shell. The female gets to about the size of a football and she swims around in open ocean grabbing small shrimps and fish. The male is about the size of a jelly bean, has no shell, mainly travels by hollowing out tubular jelly fish and driving this little jelly fish like a jet scooter out of The Jetsons, using jet propulsion to drive this little tube along, and he seems to spend his life hunting around hoping to bump into a female. And these animals very rarely come near shore; sometimes they strand and die and people find hundreds and hundreds of shells washed up but we managed to get in the water with some live ones in Port Phillip Bay late last year and they are the fastest, most spectacular animals. It's like driving around with little alien robots on jet propulsion, they can swim faster than we can so we were sort of swimming like crazy to keep up with them. They have a row of sharp spines on the edge of the shells and when you get close they turn around and ram you full speed with the spines on the front of shell, which scratched hell out of all our video camera lenses.

Robyn Williams: I can imagine yes.

Mark Norman: But this is sort of, rare footage; nobody's really filmed these things live before so it was a fantastic opportunity. We also found that they're using the shell as buoyancy control: they're bobbing to the surface, taking a gulp of air in the shell and then moderating the amount of air in it to control their level in the water and then jetting away, so it was just a very rare opportunity for us to come across such a strange animal.

Robyn Williams: Isn't that interesting, Mark because I always thought the Nautilus lived very, very deep down?

Mark Norman: Well, there's the true Nautilus, the chambered Nautilus, it's the really primitive one, and those animals used to dominate our oceans. They got to three and a half metres in diameter, these monsters sort of mini vans with squid heads stuck in the front; they're the really primitive ones, and then at the opposite stream of, or radiation of these animals you come across a fairly normal looking octopus swimming around in a convergent -shaped shell, as these pelagic ocean travellers, and these are sort of blue water drifters, they hang out in the middle of the blue water oceans, in surface waters, feeding on shrimp and fish.

Robyn Williams: And what you're saying before is that the male is so very much smaller than the female.

Mark Norman: He's tiny: so she's the size of a football, he's the size of a jellybean. When he finally bumps into a female he has this sort of, kamikaze sex system where he breaks off a special arm full of sperm, he dies and the arm independently crawls into the female's gill cavity where it hangs and is probably stored alive for anything up to months.

Robyn Williams: Do you mean she's swimming around with this arm.?

Mark Norman: With live arms, like things from the crypt, in her gill cavities and they've found females in trawl nets with six male arms wrapped around their gills, and she must wait until her eggs are mature and then feel round in her pockets for these sort of, live tetra packs of sperm, tear the caps off them and sort of sprinkle them on her eggs as she's doing her egg laying into the inside of the shell; so they hang the eggs from the inside of a shell.

Robyn Williams: Clearly she knows the arms are there?

Mark Norman: Well, who knows? I don't know actually what's going on but they'd actually be like little tiny tickling devices in the background, so - very, very strange animals. Some friends had one animal in an aquarium for three weeks, a female; she finally died. The male arm crawled out of the female - there's no male in sight - this live arm is crawling around the aquarium three weeks at least since it was separated from the male. So how the hell does this arm stay alive, how's it fed oxygen, fed nutrition? It's a real puzzle and we're trying to get a handle on that.

Robyn Williams: I can imagine. But I would have thought a rather neater way of doing it is for the male to give up its 'arm', if you like, and the sexual content thereof and then grow another one.

Mark Norman: I know, but there's been males caught quite frequently in trawl nets, there's never been a male found with a regenerating arm. The arm is half the male's body weight and their reproductive system only produces one sperm package and that sperm package gets inserted into the arm and then it's all over. So it's a sort of different form of that massive size dimorphism you get in things like deep sea angler fish, where they get six little parasitic males all sucking off blood vessels and just producing sperm. This is sort of a short-lived kamikaze version instead.

Robyn Williams: How amazing. Yes, well that discrepancy - the football to the jellybean - how extreme does that size difference get?

Mark Norman: Well, we were pretty blown away by that and then also recently we had a very rare encounter. We came across the first live male blanket octopus, which is a related family to the the paper nautiluses, and again we found a little jelly bean shaped guy swimming around and we took some photographs of him. We weighed him and he was .23 of a gram.

Robyn Williams: That's tiny. The one I'm looking at now is just gorgeous.

Mark Norman: He's a beautiful little orange guy with these deep webs on the arms with iridescent little orange spots all over the webbing and this pouch that has the modified arm developing in it ready to break off and give to the female. He was fully mature at .23 of a gram. We have measurements on females that they get up to 2 metres long and 10 kilograms, so she's 40,000 times heavier than the male is. So you're dealing with this sort of jumbo jet with this annoying sparrow kind of pecking at its tail and just after we'd found this male we got an email from the Azores in the Atlantic Ocean, where they'd come across several live females for the first time and photographed them underwater and that's one of the photographs we've got there as well. They found one of them had a live male arm crawling his way up the length of the arms towards the female's gill cavities. So it had been a very recent mating. The arm was trying to get somewhere safe where it doesn't get blown off in the current.

Robyn Williams: How does she notice she's been mated then?

Mark Norman: Well, maybe she doesn't, who knows? I mean, she may just come to the stage of laying eggs again and go, Do I have any of those sperms packets on me. And again, the multiple arms full of sperm in females that have been caught in trawls as well, so very, very strange life cycles. But it wasn't till we actually got the photographs back and started developing that we realised that one of the photographs is the first live photograph anywhere in the world of the really weird defence behaviour of these little jelly bean males. These animals must be so vulnerable out in open ocean where they could be eaten by any passing tuna or fish or trevally, or barracuda or anything.

Robyn Williams: Yes, he looks most apprehensive: that great big eye. Describe what we're looking at here.

Mark Norman: Well, we've got a little round bulbous body which is probably close to a jelly bean, a pair of large eyes staring out from that and then arms about the same length as the jelly bean, which in this photograph he's pulled back over his head - and this was as we approached the animal, it kept pulling his arms over his head. When we got the closeup photographs back and developed them we thought that we'd actually got some muck tangled on the suckers and when we looked up close they're actually little short segments of jelly fish tentacles. And it turns out that this little guy is carrying around live tentacles from jelly fish that he's removed from jelly fish and is holding like little clear pieces of rice vermicelli in his suckers as a defence. And so an animal the size of a jelly bean is packing a jelly fish punch which is probably enough to knock out a 30cm tuna that comes along and bites it, because the stinging power of some of some of these jelly fish is incredibly strong, as we've seen by recent stings and deaths associated with the Irukandji jellyfish.

Robyn Williams: Well this is quite interesting, because I've heard of that kind of use of other creatures' weaponry before, and the trick is to absorb them into your own body without setting off the mechanism.

Mark Norman: Yes, there's some little open ocean sea slugs that do it and some of the sea slugs that eat poisonous sponges and things like that, but this goes a step further. Animals like boxer crabs put live anemones on their claws and then, kind of aim the claws at whoever is having a go at them. This doesn't take the whole jelly fish; he's regularly farming fresh clean pieces of armoury from passing jelly fish and it's quite possible that these guys hitchhike on the back of jelly fish like their paper nautilus relatives do. We've got this photo from the Andeman Sea, of one of the small paper nautiluses hitchhiking on the back of a jelly fish. Like the photographer who took the photos said it took him an hour to get the photo because every time he tried to take a snap the little paper nautilus squirted jets of water to turn the jellyfish's tentacles towards the diver, and in the end he had to use two divers to even get the photograph. So it looks like this group of animals, the paper nautiluses and the blanket octopuses, have probably long associations with jelly fish and have developed immunity to their stinging cells much like the anemone fish, the clown fish, that live in the big anemones.

Robyn Williams: Well back to this little fellow's sex life. I've heard about intimidation when you've got a big beautiful woman who is just completely outclassing the little boy, but how did this come to be? Could you imagine that?

Mark Norman: Well it's something that we've been speculating on and we're writing this work up at the moment. One possibility is that both of the sexes found refuge by being small enough to use these jellyfish defences, and the females have been found from trawl captured animals to have jelly fish tentacles up to the size of 7 cms. When the females are bigger than 7 cms they never find jellyfish tentacles. So it's possible that that small size works for using jelly fishes defence; anything bigger you start to lose it. Now a male can produce tones of sperm and be that size but the female, to produce hundreds of thousands of eggs to pour out into the water to give their young a chance of survival, they need to be big body size. So we have no idea what defences the females take over once they stop doing the jellyfish things but there may have been a refuge for the male to stay hiding in that jellyfish defence world while the female got bigger and bigger and found other means of defence or other decoys.

Robyn Williams: Well obviously they can still reproduce, however tiny he is compared to her.

Mark Norman: Yes and there's a lot of parallels to things like barnacles, where the parasitic male of the female barnacle can be absolutely microscopic just living on the lip of the barnacle and all he has to do is produce sperm and that takes a fairly low energy input compared with females producing hundreds of thousands of eggs.

Robyn Williams: I suppose if it was in human society it would have a tiny testicle on tiny legs.

Mark Norman: Chasing you around a crowd or along the freeways or something and hoping to stick something on your boot that will eventually crawl to the necessary route.

Robyn Williams: Or maybe just kept in the cupboard until it's needed.

Mark Norman: A handy little purse of them on a hook, or something like that.

Robyn Williams: It would have some advantages.

Mark Norman: Yes, but I'm not advocating that for us.

Robyn Williams: Thank you.

Mark Norman: No worries.

Labels: Comportamiento

Sobre la conducta sexual del pulpo -Love that costs a leg or two-

Published by Spyder.January 23 2003

A senior curator at the Melbourne Museum, Mark Norman, has captured and photographed a male blanket octopus.

Not only is the hapless male about 100 times smaller than the female of the species, but it dies after having sex with her.

Dr Norman, who found a living one on the Great Barrier Reef, said that until now the two-centimetre male had only been discovered dead in trawls and plankton nets.

His achievement in capturing and photographing a live one has been documented in a recent paper for the New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research.

In other words, as Dr Norman told The Age: "There's no other critters on that scale that have such a significant difference between the male and the female."

The two-metre female weighs at least 10,000 times as much as the male, sometimes up to 40,000 times as much.

This could make the question of position rather delicate, but as it turns out it doesn't matter.

The male, it seems, relies on its arm as much as its penis to have sex.

This reproductive arm, known as a hectocotylus, is tucked away in a white spherical pouch between its other arms. When males mate, the pouch ruptures, the penis injects sperm into the tip of the arm, the arm is severed, and passed to the female.

It stays there until used to fertilise the female's eggs, which can be weeks later.

And while the human post-orgasm is sometimes referred to as "the little death", for the male blanket octopus the term takes on literal meaning. The male dies, but the female carries on, free to have sex with more males. In lieu of notches on the bed-post, she carries a collection of male arms carrying sperm.

"It's kamikaze sex, effectively," said Dr Norman. "They've found females with up to six male arms in the gill cavity."

But how did it get that way? Males compete with each other to fertilise the female, said Dr Norman.

Being small allows the male to mature earlier, and allows for better self-protection using its tentacle segments.

Both the male and female species are lodged with the collections at Museum Victoria.

Labels: Comportamiento

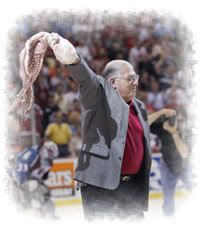

Pulpos y el hockey

Published Saturday, September 09, 2006 by Spyder. Existe una tradición muy curiosa entre los fans del equipo de hockey americano de los Detroit Red Wings, los cuales en la temporada de playoffs lanzan siempre algún pulpo a la pista de hielo; el pulpo ya está muerto, por si algunos dudaban...

Existe una tradición muy curiosa entre los fans del equipo de hockey americano de los Detroit Red Wings, los cuales en la temporada de playoffs lanzan siempre algún pulpo a la pista de hielo; el pulpo ya está muerto, por si algunos dudaban...Octopus On Ice

Labels: Curiosidades

Pupos y el hockey -Legend of the octopus-

Published by Spyder.

Labels: Curiosidades

Ignacio Aldecoa -Entre el cielo y el mar-

Published Friday, September 08, 2006 by Spyder."La red iba saliendo lentamente a la áspera playa. Su dulce color de otoño, roto por la lucecilla plateada de un pescado muy chico o por el verde triste un alga prendida en sus mallas, dividía la oscura desolación de grava menuda; cerca cabeceaba la barca vacía. Los niños pisaban la red. Pedro había asumido la labor de espantarlos. Decía una palabrota y hacía que corrieran apenas unos metros para pararse en seguida y volver confianzudamente a poco. Pedro tenía entre los labios el chicote de un cigarrillo y les miraba superior y hostil, porque era casi un hombre y trabajaba. En el copo había un parpadeo agónico y blanco de pascado y se movía la parda masa de un pulpo con algo indefinible de víscera o de sexo. Un último esfuerzo. Los pescadores se inclinaron más; luego se irguieron en silencio y contemplaron el mar. La tercera vez en la mañana. El señor Venancio, el de la nostalgia de los tiempos buenos de la costera, dio una patada al pulpo, que retorció los tentáculos, y, al fin, medio dado la vuelta, los extendió tensamente, abriéndose como una rara flor"

Ignacio Aldecoa -Entre el cielo y el mar-

Ignacio Aldecoa (Vitoria 1925-Madrid 1969) fue un narrador excepcional y uno de los escritores más importantes de la narrativa española de la segunda mitad del siglo XX y con el paso del tiempo no ha dejado de obtener un refrendo cada vez más amplio de la crítica y el público. Aldecoa, pese a su breve vida, fue uno de los mejores autores de cuentos de la literatura española contemporánea, recuperado por la crítica y el público treinta años después de su prematuro fallecimiento, como demuestran títulos como Vísperas del silencio (1955), El corazón y otros frutos amargos (1959) y Caballo de pica (1961). También nos dejó magníficas novelas, como El fulgor y la sangre (1954), Con el viento solano (1956) y las inolvidables: Gran Sol y Parte de una historia (1967)

Labels: Literatura

Sobre la conducta sexual del pulpo -Reproductive behaviour of the blue-ringed octopus-

Published Thursday, September 07, 2006 by Spyder.CHENG M. W. ; CALDWELL R.

Labels: Comportamiento

Pulpos -Dibujos- El pulpo Manotas es gay-

Published Wednesday, September 06, 2006 by Spyder. Si hablamos de Squiddly Diddly seguramente no sabrán de que les hablo. Pero tal vez sí -al menos los que pasan la treintena- si que recordarán al Pulpo Manotas. Un pulpo que hacía vivía en un parque acuático y continuamente se intentaba escapar de allí, burlando la vigilancia del dueño, el Sr. Alférez Pérez (en la versión inglesa Chief Winchley).

Si hablamos de Squiddly Diddly seguramente no sabrán de que les hablo. Pero tal vez sí -al menos los que pasan la treintena- si que recordarán al Pulpo Manotas. Un pulpo que hacía vivía en un parque acuático y continuamente se intentaba escapar de allí, burlando la vigilancia del dueño, el Sr. Alférez Pérez (en la versión inglesa Chief Winchley).¿Recuerdan al Pulpo Manotas gritando aquello de “ay Mamá Pulpa”?

Lo curioso es que la versión original inglesa el pulpo es en realidad un calamar (squiddly) aunque realmente tiene aparencia de pulpo, por lo que no se descarta que sus creadores de la Hanna-Barbera quisieran dotarle de una mentalidad trastornada desde su más tierna infancia: un profundo problema de identidad, sumado a un exceso de influencia materna, un cierto amaneramiento en sus gestos, su color rosado y su voz aflautada... (lo vimos en algún capítulo vestido de marinerito dispuesto para arrancarse con el In the Navy, y si no atiendan a la imagen). Todo ello, me hace preguantarme. ¿cuales pudieron ser los motivos de los dibujantes de Hanna-Barbera para ser tan crueles con su propia creación?

Labels: Dibujos

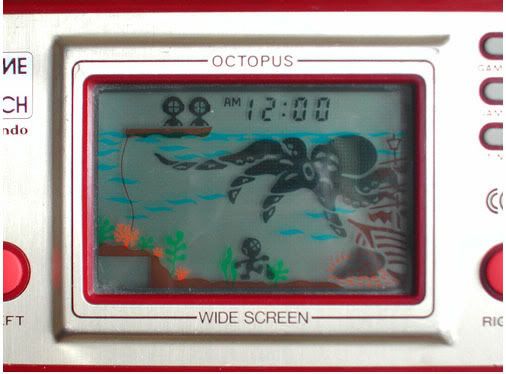

Juegos de Pulpos -Nintendo Octopus-

Published Tuesday, September 05, 2006 by Spyder.Todo un juego de pulgares, uno para dirigir al buzo hacia la izquierda y el otro para que fuera hacia la derecha, todo un ejemplo de sencillez opuesto a los juego actuales donde existen quince botones que realizan acciones distintas.

Y por si hay incrédulos, el juego enganchaba, porque hay una cosas que siempre es adictiva, y es el superar el record que ha puesto otra persona.

En Handled Games Museum se pueden encontrar la mayoría de estas maquinitas prehistóricas que tanta compañía nos hicieron. Otro dia hablo de mi Spectrum 48 K.

This is a review of a hand-held game "Game & Watch" made by Nintendo (makers of the Donkey Kong video arcade game). The model I have is called "Octopus". The store where I bought mine had five different models, each costs $35.

First a general description of the physical configuration. The case is quite thin; about 3/8 inch thick, 4 1/2 inches long, and 2 2/1 inches tall. About the size of a wallet calculator. It has a large LCD screen in the middle. The dimensions of the screen are 2 1/8 inches by 1 3/8 inches. The game is held with the long dimension horizontal. To control the action there are two large red buttons, one on each side of the screen, each conveniently near the lower left/right corner where your thumbs would naturally rest. The left red button causes movement to the left and the right red button causes movement to the right. In the upper right hand corner are three buttons; two select the level of difficulty, game A and game B, the third button turns on the clock display as the game can be a clock while it isn't being used. It has a little swing out stand in the back so that it can be stood up on your desk.

The game: to get as much of the treasure out of the sunken ship as possible. The scenario: in the upper left corner is your boat floating on the surface of the sea with a rope dangling to the ocean floor, in the lower right corner is the sunken ship with the treasure chest. Filling up most of the area in the water is a large octopus with four tentacles that grow and shrink at random rates and intervals. The rightmost three tentacles don't move around, they just grow and shrink. The leftmost tentacle can grow either in a downward direction or in an upward direction. In the upward direction it can snag you while you're climbing down the rope. If one of the tentacles touch you you're dead. As the game starts you have three divers in the boat and you use the right button to move the first one down the rope and over to the treasure then you use both buttons to make it dance back and forth to avoid the tentacles or when you're all the way over to the treasure you press the right button to make it grab some of the treasure. For each piece of treasure you snatch you get one point. After you've picked up any amount of treasure you can climb back into the boat and get a three point bonus. While the game is being played it makes a ticking sound; reminds one of a time bomb and adds to the sense of tension and panic. When the octopus gets you the game makes a buzzing rasberry sound and the remaining diver(s) do a left shift in the boat in preparation for the leftmost one going down next. Game A and B are the same except the tentacles move faster in game B.

It's quite fun. It's difficult enough to keep you coming back but not to difficult to frustrate you. The design of the characters is very humurous. The octopus has a sappy, lugubrious expression. When the diver is grabbing some of the treasure it's arm moves back and forth from the treasure chest to the bag it's stuffing it into. When it gets back into the boat it's arm swings up and down with the bag to show it unloading the treasure. They have comical positions when walking over to the treasure. When the octopus gets one of the divers he pulls it up towards him and the diver flails its arms and legs frantically.

Features: As mentioned before it has a clock. When the game isn't being played it can stand up on your desk as a clock with the time displayed in the upper right hand corner of the screen. While in clock mode the display is active with the divers marched down to the treasure and pranced around until the octopus gets them but it is all done silently with no ticking or beeping. It also has an alarm. The clock and alarm are 24 hour.

Misfeatures: to set the clock or alarm requires a thin object to poke the recessed buttons. A paper clip straightened out will do. It remembers the highest score but setting the clock causes it forget it. There is no on/off switch (being LCD I suppose that's not a misfeature).

Labels: Juegos

Un pulpo macho a la hembra...

Published Monday, September 04, 2006 by Spyder.Te doy:

Mi mano

Mi mano

Mi mano

Mi mano

Mi mano

Mi mano

Mi mano

Mi mano

Labels: Humor

Literatura y pulpos -Sakutaro Jaguiwara-

Published Sunday, September 03, 2006 by Spyder.Sakutaro Jaguiwara

Todo el mundo se olvidó de este lóbrego acuario. Era de suponerse que el pulpo debía estar muerto y sólo podía verse el agua podrida iluminada apenas por la luz del crepúsculo.

Pero el pulpo no había muerto. Permanecía escondido detrás de la roca. Y cuando despertó de su sueño tuvo que sufrir hambre terrible, día tras día en esa prisión solitaria, pues no había carnada alguna ni comida para él.

Empezó a comerse entonces sus propios tentáculos. Primero uno, después otro.

Cuando ya no tenía tentáculos empezó a devorar poco a poco sus entrañas, una parte tras otra.

En esta forma el pulpo terminó comiéndose todo su cuerpo, su piel, su cerebro, su estómago, absolutamente todo.

Una mañana llegó el celador, miró dentro del acuario y sólo vio el agua sombría y las algas ondulantes. El pulpo había virtualmente desaparecido.

Pero el pulpo no había muerto. Aún estaba vivo en ese acuario mustio y abandonado.

Por espacio de siglos, tal vez eternamente, continuaba viva allí una criatura invisible, presa de horrenda escasez e insatisfacción.

Vía Texto Sentido

Labels: Literatura

Chiste -El pescador y el pulpo-

Published by Spyder.En ese momento ve venir a la guardia costera y nervioso coge al pulpo y se lo echa por el hombro.

- ¿No sabe usted que está prohibido pescar pulpos?

El pescador mira al pulpo incrédulo y responde al policia:

-Ya le decía yo a este puñetero bicho que nadie se iba a creer el cariño que me ha tomado.

Labels: Humor

Mitología del pulpo -Charles Montgomery-

Published Saturday, September 02, 2006 by Spyder.

Can the myths of the Lau Lagoon clan survive their preservation?

by Charles Montgomery

Partly because of empire, all cultures are involved in one another; none is single and pure, all are hybrid, heterogeneous, extraordinarily differentiated, and unmonolithic.

They are saying terrible things about the anthropologist Pierre Maranda in the Solomon Islands.

You could call this story a myth, which is to say that historical accuracy is irrelevant to its truths. The archipelago that surrounds the Lau Lagoon has gained a reputation as a veritable Disneyland for anthropologists interested in this kind of narrative. The big guns of early twentieth century anthropology—Bronisław Malinowski, W. H. Rivers, Maurice Leenhardt, and others—were convinced by their time in Melanesia that the real function of mythic stories was not to entertain but to serve as vehicles for moral and existential truths. They carried rules for living, values, messages from the ancestors. They told islanders about the most essential parts of themselves. They were metaphors, yes, but they were always sustained by lived experience. And as far as the islanders were concerned, whenever they obeyed the rules set out by their ancestors, they prospered.

I met Pierre Maranda at Université Laval on a June afternoon nearly two years after first hearing his name. Maranda wanted to show me his backyard. As we roared through Quebec City in his 1982 Turbo Porsche it was hard, at first, to judge the then-seventy-four-year-old anthropologist’s reaction to the strange accusations levelled at him. Not because he was incommunicative, but because his eyes were necessarily hidden behind a pair of wraparound sunglasses. His left cornea had been permanently scarred by the surface glare of the Lau Lagoon.

Maranda returned to the lagoon seven times over the next two decades. With each visit he found the pagan priests more anxious. Seventh-day Adventist missionaries had launched a crusade in the lagoon. The Adventists brought generators and loudspeakers so they could broadcast the Gospel for miles around. They said the spirits” —including the one that resided inside the Foueda octopus—were devils working to trick people on behalf of Satan. The priests told Maranda of the shouting matches they would have with Adventist missionaries on market days. The missionaries would arrive with colourful posters depicting heaven and hell. “If you remain wikita, this is where you will go when you die,” they warned the pagan priests, pointing at the fires of the underworld. “At least we will get to spend eternity with our own ancestors,” the priests would respond.

In Melanesia, traditional knowledge has depended increasingly on foreign writers for its survival since the missionaries arrived in the late 1800s. Sometimes islanders forgot their pagan myths after their Christian baptism. Sometimes they censored themselves under pressure from missionaries. These days, some communities trying to revive old traditions have no choice but to turn to written accounts for guidance.

Nearly a year later, I reach Maranda by phone as he is preparing to fly to Paris for a meeting with Lévi-Strauss and then a team of information managers. The Lau data must be digitized, he says; it must be recorded, remembered. This is what anthropologists do.

Charles Montgomery is the author of The Last Heathen (Douglas & McIntyre, 2004), which won the 2005 Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-fiction.

Labels: Mitología